|

Sub-headings for this page:

Mining by hand to 1700:

Mining 1700 to present day:

Housing

Illness & accidents

Strikes & unrest: (Seven

periods of dissatisfaction described)

In the miners own words: (A

dozen people interviewed in 1842)

Introduction Lead and zinc were the chief minerals found in veins throughout most of the Halkyn Mountain area. The abundance of lead created an area of national importance with a history stretching back at least 2000 years. Today all mining has ceased. The last mine closed in 1987. Most surface mine buildings and machinery have now disappeared. The surface of Halkyn Mountain today exhibits a landscape pock-marked with countless workings and old shaft craters. Although virtually no records remain of the earliest workings, the existence of records from the 13th century enable the reader to form a reasonable picture of the industry since then. The following is not a full or thorough history but merely intends to convey that picture.

The information below originally described the story of lead

mining at Halkyn Mountain, but the conditions and methods

described apply equally to lead mining throughout Flintshire

and Denbighshire. The information was compiled from a mix of

original research and material already published. I was

asked to write it in 2004 as part of the Halkyn Mountain

Interpretation Scheme. It has been slightly amended for this

website.

Sincere thanks to 'Ian Parkin Heritage & Tourism' and 'Cadwyn

Clwyd' for permission to reproduce this work.

Some parts have relied heavily on information researched by

Bryn Ellis in his detailed and fascinating “History of

Halkyn Mountain.”

Click on any image to view full size (then use the BACK button to continue)

Mining

by Hand to 1700

The early miners

A lead vein is a mineralised fault or crack in the earths crust. Some veins would have been clearly visible on the mountain as grey bands running over the surrounding white limestone rock. The soft maleable mineral must have attracted the interest of people long ago, but the first people thought to have mined for lead in North Wales were the Romans who had interests on Halkyn Mountain and at Minera. It is not known how much mining was being carried out in those times, but they may not have mined more than a few metres below the surface as ore was plentiful. In fact, lead was found in such abundance in some areas that a law was passed to limit production.

After the Romans left Britain around 440 AD, it appears that

very little mining was carried out for about 800 years. It

was not until medieval times that mining was again carried

out by farmers who began small-scale mining as a means to

supplement their incomes. These farmers either worked from

the bottom of the Roman workings or searched for ‘new’

undiscovered veins on the surface. As the veins

were steadily worked deeper and deeper, flooding became a

serious problem and many veins had to be abandoned. This

flooding problem dogged the industry for most of its

history.

Possibly from around 1000AD mining laws were introduced

which gave miners many rights and priviledges (see Ancient

Mining Laws below). These allowed any miner to enter a field

belonging to someone else and begin mining. If he found lead

ore, he would be allocated a certain area of ground along a

vein measured in Meers; a meer in Flintshire being 30 yards.

In 1282 (after the English conquest of the Welsh Princes) a major castle building programme revitalised the industry. Many churches and abbeys also needed repairs and lead was much needed for roofing, plumbing and drains. In 1296, Edward 1st ordered many Flintshire miners to work in the silver mines of Devon to produce coinage. In these early years, most mining was carried out by small groups of farmer/miners who worked underground in dry periods when water levels were at their lowest. Lead mining production eventually increased dramatically in the late 1600s with the introduction of improving technologies together with financial investment brought in by mining companies who saw the potential that the industry offered. The industry reached its peak around 1870 after which many mines closed under the threat of falling ore prices due to imported ore. Some mines however, were rejuvenated by the driving of two major drainage tunnels: The Halkyn (or Old Drainage) Tunnel and the Milwr (or Sea-level) Tunnel. The latter was extended to a total length of 10 miles by Halkyn District United Mines Limited and continued to produce ore until about 1978.

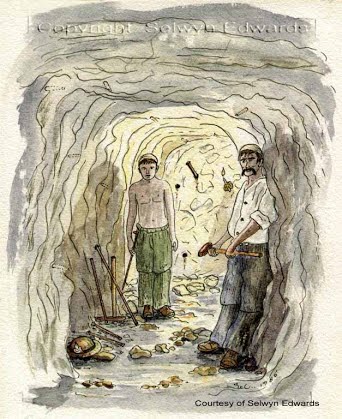

Pick & Shovel

The basic tools needed to extract ore from the

ground changed little for about 1700 years: The pick,

crowbar, hammer, chisel, wedge and shovel. The ore itself

was soft and yielding and was generally easy to pick from

the vein. Loose ore would then be shovelled into wooden

buckets or sledges to be takern to the nearest shaft. In

some mines, wheel-barrows were preferred for this job.

Barrowing was made easier by the laying of planks along

passage floors. When a lead vein in the roof of a passage

was being picked, a canvas ore-sheet might be laid along the

floor to catch the falling pieces. An ore-sheet from 1883

lies in place and undisturbed today at North Hendre Mine.

Firesetting

Progress would have been steady unless a passage had to be

driven through the surrounding harder rock. On Halkyn

Mountain the native rock was mainly limestone (or chert,

in the area to the north-east) and was much harder than

the vein material. In the days before gunpowder or high

explosives, fire was used for ‘mining’ a tunnel through

hard rock in search of lead ore. The process was known as

‘firesetting’ and was in use from ancient times until

around 1700 when gunpowder was first introduced in local

mines.

The technique involved simply lighting a fire against a rock face. The heat generated would crack the surrounding rock allowing it to be picked away albeit slowly, by hand. The process was far more effective if water could be thrown onto the heated rock to cause rapid cooling: Agricola in 1556 suggested that the application of vinegar was most effective. If a passage roof needed to be removed, a platform would be constructed supporting a bed of stones. The fire could then be built upon the stones, thus applying the heat to a specific area. It was important to use the hottest fuels such as “cord-wood, coal or horse bones” (Hooson 1747). The most effective fires were those which had a good supply of air. It was possible in some mines to provide air by constructing a flue built into the passage floor known as a ‘fang’ (Hooson 1747). Air was encouraged underground by installing wooden 'boxes' over particular shafts; one side of the box was open and was rotated to face into the prevailing wind (in a similar fashion to ventilation pipes on the deck of a ship). Firesetting was normally done at the end of the day and allowed to burn overnight. The following morning all loose rock could be removed and the remaining slightly fissured rock could be slowly freed with hammer and chisel. This was extremely slow and laborious work. Tunnelling rates of 2 or 3 metres a month were typical. By 1700 gunpowder was beginning to replace firesetting in most mines as a preferable alternative.

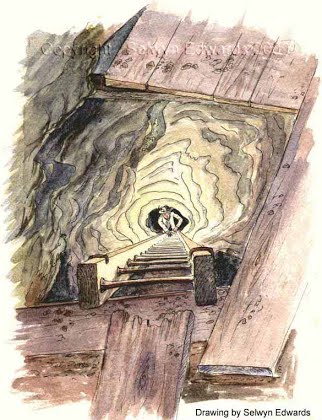

Shafts

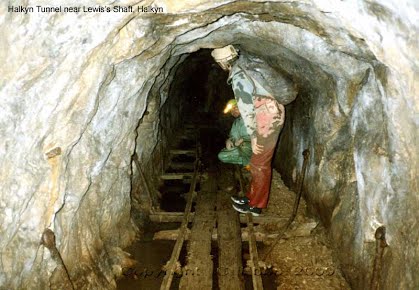

and levels In order to reach a lead-bearing vein, shafts would be excavated vertically from which horizontal passages known as levels would be driven off. When a body of ore was found, the entire deposit would be removed before extending a level or deepening a shaft. Many workings on Halkyn Mountain consist of a single trial shaft, perhaps 10 metres deep, with a short level off in search of ore. If unsuccessful, it would be abandoned as miners moved on to try their luck elsewhere. Many of these trial shafts were excavated by small groups of perhaps 3 or 4 men. If successful, they would either work the ore themselves or, as occurred in later years, sell their workings to a neighbouring mine company.

Raising

to Surface Ore was normally shovelled into wooden buckets with iron hoops to be carried to the nearest shaft or was put on wooden sledges to be dragged along a passage floor by rope. An old wooden sledge remains today in the workings of North Hendre Mine. The buckets or sledges were then emptied into larger buckets or ‘kibbles’ to be raised to surface by means of a simple hand-operated windlass. At deeper shafts, a horse whim might be erected consisting of a large winding drum rotated by one or two horses. As mines became more extensive, rails were laid along main passages and ore was transported in wheeled wagons.

Early

pumping Pumping water from mines in the early years was difficult. Most wet mines on Halkyn Mountain relied upon wind power to drive crude and inefficient pumps. ‘Rag and chain pumps’ were used in Flintshire which operated by pulling a metal chain through hollowed logs or metal pipes. Balls covered in horse hair were built aaround the chain at intervals and these were able to lift water when the chain was pulled through the pipe. Although rag and chain pumps are known to have been used throughout Europe for at least two hundred years, they must have had a limited effect and were only able to operate on windy days. A modern hand-operated version of the rag-and-chain pump (using wire instead of chain and large washers instead of rags) is used today to provide water in many under-developed countries. Where water was freely available, water-wheels provided a far more reliable energy source, but on Halkyn Mountain water was scarce and other solutions were desperately needed at many mines.

Ancient

Mining Laws The Black Death hit the area in 1349 when a quarter of the population died. Men refused to work the mines and little mining was carried out. In an attempt to stimulate lead production, ancient Mining Laws were re-introduced into the area in 1352 by Edward the Black Prince. The origins of these laws are unclear but they may have existed from around 1000AD. Early mining was for many years controlled by these laws which are similar to those still upheld in Derbyshire today. Strict procedures governed the industry and grievances were dealt with at a Barmoot (or Barmote) Court convened for the purpose and presided over by a Barmaster.

The laws are set out in a

detailed register preserved today in the Public Records

Office. The following extracts have been translated from the

original Anglo-Normal French and simplified (see C. J.

Williams in Bibliography for full article on mining laws) and

are simply an example of some. The complete set of mining laws

cover many pages:

If the Barmaster finds a meer not being worked, he shall have the meer marked (nicked) on three successive weeks. If it is still not being worked on the second day following the three weeks, the miner will forfeit the meer to the lord (landowner).

The Barmaster shall allocate every miner working on the vein a plot to build a house and the right to take wood to repair his house or fence. The miner may also take whatever timber he needs for his workings.

Miners shall not pay rates or taxes so long as they pay the lord 2p a year. This also allows the miner to graze his animals on the lords property except in parks, meadows, sown fields or designated wastes.

If anyone is found guilty of stealing ore, the fine shall be 25p for the first offence and 50p for the second offence. For a third offence, his right hand shall be pierced with a knife through the palm and pinned to the drum of the windlass up to the handle of the knife. And there he stays until dead or frees himself, in which case he shall forfeit any rights to the mine and his meers.

The mining laws applied in Flintshire were based upon

similar Derbyshire mining laws. These are still upheld today

in Derbyshire where Barmoot Courts are still presided over

by a Barmaster.

Involvement of the Grosvenor family Sadly the old and interesting mining laws were not to last. Richard Grosvenor first came into possession of a few mines in 1601 by holding short-term grants or leases. The Grosvenor family then began aquiring other local mineral grants. In 1614 Richard Grosvenor was granted rights by the Crown which effectively gave him control of the mines. A radical move was to abolish the miners laws in 1623. This caused great conflict with Halkyn miners who claimed their historical right to mine for lead. A court case followed which resulted in victory for the Grosvenors and the mining laws were extinguished. Most mining since then has been carried out by leasing the rights to mine from the Grosvenor family who today still own mineral rights over most of Halkyn Mountain. Other large landowning estates also issued mining leases, such as the Lords of Mold who own many of the lead veins between Rhydymwyn and Loggerheads. With the

mining laws crushed, the Grosvenors were then in a position to

begin managing the industry in a more organised fashion and

gradually production and profits began to increase.

Mining 1700 to present day

Gunpowder Blasting The first major technological inovation in mining was the introduction of gunpowder for blasting from around 1680. For the previous 1700 years, all mining had been carried out entirely by hand with the aid of ‘firesetting’ to crack the hard limestone rock achieving at best, tunnelling rates of 2 or 3 metres a month. Although gunpowder was first used in mines around 1680, it took another 50 years before most mines fully adopted its use. This delay was due to the fact that methods used were initially very unsafe. Many miners were injured or killed before the technique was improved to a then acceptable degree and tunnelling rates began to increase by up to three times that of firesetting.

The method used in blasting first involved the drilling of a hole by hand. This was done by hammering a drill ‘steel’ perhaps 3 feet long by almost an inch in diameter. With each blow of the hammer, the steel would be turned a little in the hole before the next blow. When deep enough at perhaps one metre, the hole would be cleaned out with a long thin metal scraper. Powder was then poured into the hole leaving perhaps a third of the hole empty. A fuse would then be gently pushed down the hole into the powder leaving its end hanging out of the hole. Sand was then pushed into the hole and tamped down to form the ‘stemming’. Several holes could be set at one time. When ready, their fuses were lit and the men would move to safety. Unless the passage was well ventilated, the men might not return until the next morning when the poisonous fumes had cleared. When safe to return, the broken rock was shovelled onto wooden sledges or into mine wagons to be taken to the nearest shaft up to surface. A common practice was to use lead dust instead of sand as stemming. The resulting airbourne lead particles from blasting added considerably to lead poisoning statistics.

In 1878 the ‘high explosive’, dynamite was introduced. This was far more effective for tunnelling and the use of gunpowder rapidly died out.

London Lead Company In 1692 the Grosvenor family introduced leases demanding royalties on the ore produced, commonly a twelfth or thirteenth of the total. This led to a downturn in production and the Grosvenors sought outside investment. Two Quaker men from London then took up 21 year leases on Long Rake and Old Rake at Rhesycae. They did well and within 3 years had invested £5000 and became the London Lead Company. They introduced many technological innovations. By 1709 this company was producing 1000 tons of ore a year; more than all the other local mines combined. The company transformed their mines from small-time mining ventures into mines that were highly organised and productive, paving the way for the many companies that followed. The company eventually left the area in 1792 at a time when ore prices were slumping.

During the 1700s, many mining companies moved in to exploit the areas mineral resources. Some small groups of miners continued to work on their own and were known as 'adventurers' or 'cavers'. Many others joined the new companies although they paid for their own tallow candles and gunpowder which they bought from the company store. Although some adventurers did make small fortunes, the majority struggled to survive. It was the larger companies who began to dominate the industry, strengthened by their ability to plan ahead and invest in new technology, that enabled the industry to survive into the 20th century.

The lead rush of 1715 In 1715 an exceedingly rich vein was discovered in a field just to the south-east of Pentre Halkyn village belonging to George Wynne of Leeswood. He brought in miners from Derbyshire to work the mine. The discovery developed into to a ‘lead rush’ in the area which attracted further Derbyshire men; investors, managers and skilled miners followed by labourers. Derbyshire names such as Bagshaw, Ingleby, Harrison, Hooson and Oldfield became well-established in the area. ‘Profit fever’ was such that leases were even granted for mining within the grounds of Halkyn Church and beneath a main road.

Further large discoveries helped to secure a promising reputation for Halkyn Mountain such as at Silver rake in 1750. In 1770 a rich find at Rowley’s Rake (Pant-y-pwlldwr) produced ore valued at over £1,000,000. At Brynford in 1774 another mine made £100,000 in a few years. The last large discovery of the century was at Great Holway Mine in 1798 which continued to supply large quantities until 1825.

Although people invested heavily in the hope of large profits, many failed to find the rich deposits hoped for. Consequently several large estates became bankrupt and some individuals ended up in the ‘debtors prison’.

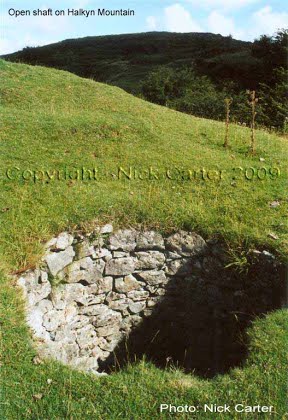

Mining Landscape Mining was commonly carried out by small groups of men who were granted annual licences known as Bargains. This encouraged them to try their hands at prospecting and many local people scoured the mountain for new discoveries. Consequently, many of the thousands of small shafts which pock-mark Halkyn Mountain were simply trial shafts. Old shafts small and large, still exist throughout Flintshire's lead mining areas. A few of these exceed 200 metres in depth. The Grosvenors attempted to ensure that old shafts were filled or covered but this was unsuccessful and scores of shafts remained open and dangerous for many years. A project in the 1980s successfully sealed nearly 200 of these shafts and today only a few dozen are known to remain open. As well as the pock-marked surface, the landscape still displays the remains of various ore washing floors, whim shaft circles, crushing stones, tips of waste rock and the foundations of old mine buildings. The remains of a few engine houses still remain and some mine buildings have been converted into residential properties.

Modern day collapses Many lead mining shafts were covered over at the surface and their locations are now not known. Shafts were normally stone-walled down to the depth of solid rock. The walling at this depth was often built upon a timber collar. With the passing of time, these timber collars rot away and the dry stone walling then collapses leaving a crater on the surface so typical of those on Halkyn Mountain. When discussing shafts of similar diameter, the size of a crater depends upon the depth from surface to the solid rock below. Obviously a shaft of larger diameter will also result in a larger crater.

Lead, silver, zinc and limestone Lead ore (galena) was the chief mineral mined at Halkyn Mountain. Its uses have included the manufacture of batteries, bullets, roofing sheets and drain pipes; an additive in the manufacture of paint, cosmetics and as a whitener in bread etc. Seven hundred years ago it was also used for making lead brine pans used at Cheshire’s salt mines.

Silver was extracted in small quantities as a by-product of galena, in varying amounts from 6 to 18 ounces per ton. It was used for jewellery and coin production. Silver coins minted in Flintshire were stamped with the Royal emblem of the plume and feathers.

In 1720 it was realised that calamine had a value and this was mined is small quantities and used for brass making.

Zinc ore (blende or blackjack) was initially thought to have been worthless. However, the invention of the galvanising process (involving the use of zinc) in 1837, led to a huge demand for products and kept many mines in profit after the 1870s when lead prices were in decline.

Limestone suprisingly, was mined (as opposed to being quarried) in large quantities between 1939 and 1969 when up to 80,000 tons a year were being extracted. The stone was considered to be of the highest quality by Pilkington’s who used it in the glass manufacturing process. It was also used as fertiliser. Most of this stone was mined from the south side of the mountain just north-east of Hendre village, although some limestone mining was carried out from Pen-y-Bryn Shaft at Halkyn. The chambers created at Hendre are enormous and cover several acres. Steam Engines and Drainage Adits

As mines became deeper, flooding became more severe. In many

cases, mines could only work during dry Summer periods

or had to be closed. Two methods were adopted to counter the

problem: deep drainage adits, or horizontal tunnels

that were driven into mines where the topography was

suitable, and steam pumping engines.

Drainage adits required costly investment in both time and

expense, particularly as they were generally driven through

hard rock, rather than along softer vein materials. Hence,

drainage adits were seen as long-term investments. Scores of

these adits were mined, frequently from fairly shallow

locations, permitting perhaps a few years further production

before workings reached depths below the adits and once

more, suffered from flooding.

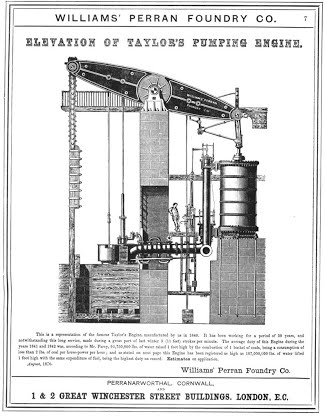

Print taken from a "Catalogue of Pumping &

Winding Engines" manufactured by Williams' Perran Foundry

Company, Cornwall, dated about 1870.

Reprinted by the Trevithick Society and

available for around £5 ISBN 0 904040 02 X

During the heyday of mining in the 1860s, many local mines had several Cornish engines operating together keeping the deeper workings free from water. These engines were basically coal-fired boilers operating a large single cylinder, commonly with pistons over 7 feet in diameter. These large machines created a slow but powerful up and down movement of the piston, which was connected in turn to a heavy cast-iron beam, one half of which projected out from the top of an engine house. Long heavy timbers known as pump rods were then attached to the beam and hung down the shaft. A pump was then connected to the bottom pump rod and water was forced to the surface up sturdy cast-iron pipes known as 'rising mains'.

The beam of a Cornish engine operated at about 8 strokes per minute and was capable of working continuously for 6 months at a time or more, under a load of 56 tons. When mines closed, engines were frequently sold to neighbouring mines or were taken to other mining districts. Many were given names such as Queen of the Mountain and gained grand reputations commensurate with their pumping ability.

To be an engine driver, as the operator was called, was not an easy task. Mastering the controls required "great skill and nerves of steel". Keeping the pressure under control was a matter of operating several levers. Many early engine boilers exploded due to imperfect handling, but this was overcome by the invention of pressure release mechanisms (the Climax Relief Valve, being one), much to the relief of engine drivers everywhere.

Output Imported lead ore from Europe began to put pressure on the industry from 1825. But optimism remained high and more and more companies continued to invest in the area. By 1845 Flintshire was producing record figures of 10,000 tons a year and employing nearly 3,000 people. The next peaks were not until the 1890s with 8,000 tons and the 1930s with 20,000 tons; both due entirely to the driving of deep drainage tunnels.

The most accurate records of production cover the years from 1845 to 1938. Throughout the whole of this period, Flintshire produced nearly 500,000 tons of lead amounting to 10% of the UKs total.

Such figures give the impression of a generally healthy industry. However, throughout the areas mining history, the story is one of constant boom and bust. One year of large profits could easily be followed by another of depression or closure. Over the years, mines were repeatedly re-opened or closed as flooding or price fluctuations dictated.

Housing

Miners

cottages

It was customary practice in most UK metal mining districts

for miners who could afford it, to take waste land and build

their own homes. This would, of course involve a great deal

of time and effort. It would also cost the equivalent of

many months wages. In 1861 a miners cottage could be built

for £50 to £100. It was generally simple housing consisting

of a living room with two bedrooms above. The floor would be

made of compacted earth or flag -stones. These cottages

would have been similar to those of non-mining families of

the time.

Such miners therefore lived in their own freehold properties which gave them an independence that was much prized. This irritated an Agent for the Grosvenors who said “I cannot understand why a miner would choose to build his own home for £100 rather than rent a comfy cottage for £2 a year”.

In 1842 Halkyn miners homes were described as “neat

though scantily furnished”. “Most had at least a rag rug to

soften the hearth”. In the years that followed,

clocks were to be owned by most mining families. Metal

cutlery then became the next functional addition. China and

other ornaments then began to appear, marking the beginnings

of the consumer society so prevalent today.

Most mining families on the Mountain were very poor,

particularly at times when mines were closed and no wages

could be earned. Such times were presumably being described

in the following two grim accounts of miners housing,

although it seems likely that these may have been extreme

examples......

A Government Enquiry in 1846 heard that “Some

miners cottages consist of a single room from 9 to 12 feet

square; others have in addition a lean-to, forming a

separate place to sleep in. They are in general devoid of

furniture, the roofs are wattled others are of straw, and

full of large holes open to the day”.

Parliamentary Papers in 1864 further state that the lead mining community of Halkyn was criticised for bad ventilation and drainage. “Cesspools were too near houses and there were constant outbreaks of typhus and scarlet fever”.

Miners barracks

It was common at mines throughout Europe to provide accommodation for miners who did not live locally. At Halkyn Mountain a barracks still survives near Pant-y-go Mine between Rhosesmor and Halkyn. Miners would normally stay in barracks during the week, for which they paid 3 pence in 1888, and returned home for the weekend.

It was noted in 1888 that some European mines had barracks

which were warm and roomy with heated changing rooms. Those

in Wales however were described as “Dirty,

disordered and uncomfortable places, where men slept two to

a bed”, but this may have referred to those of

mid-Wales. Moves were made to improve conditions in Welsh

barracks but the decline in the industry at that time meant

that any such plans were shelved.

Illness & Accidents

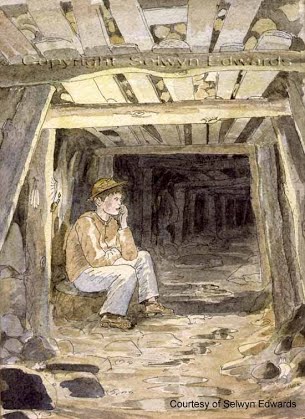

Carbon dioxide poisoning

Poor ventilation was common in many local mines and created dreadful working conditions. As men and candles used up oxygen in the air, carbon dioxide was created. Known by miners as ‘the damps’, this caused men to fight for breath and go red in the face. In only small concentrations a candle flame struggles to burn or will extinguish. Working in bad air was simply accepted as an occupational hazard on the Mountain although in high concentrations, it could be fatal. Higher rates were paid to miners working in badly ventilated areas as a means of inducement. A Derbyshire miner, William Hooson, who came to work the mines of Flintshire wrote a fascinating “Miners Dictionary” in 1747. He describes “unsavory damps” thus…. “The Air is thick and muddy, making him Pant and Blow, and Sweat, with a Pain and Beating in his Head and Stomach; and when he comes to the Day into the fresh Air, he is troubled with a Giddinefs in his Head, and fometimes with Vomiting” .

Lead poisoning

This was a common accurrence and was known by miners as

‘bellan’ (or belland). Typical symptoms included

constipation and cramp, vomitting, poor appetite, weight

loss, anaemia, muscle weakness, headaches. Others symptoms

were described as “Dull

skin, a clammy body with perpiration and blue gum”.

Blue gum was a distinctive thin black line over the gums

indicative of lead poisoning. The problem was not helped by

the practice of ‘stemming’ (filling) shot-holes with lead

dust instead of sand.

Although there was no known cure, miners attempted to alleviate the symptoms by taking bread dipped in sweet oil and taking no alcohol.

On the surface lead poisoning was known to have been a

problem for animals. Cattle and sheep were prevented from

drinking contaminated water that ran off from the washing

areas, tips and settling ponds. In 1780 a farmer near

Maeslygan Mine at Halkyn was given compensation of £3-15-0

for a mare and cow that died from bellan.

Hooson describes lead poisoning as……. Belland: The name of a diftemper that Miners are often fubject to, the Miner is not seized with it, but in Working upon hard Ore, the Duft whereof that arifes from his Pick-point, being a very Sulphureous Smell, gets into his Bowells, and causes a strange Coftivenefs, with Intolerable Pain for many Days together, (oftentimes) and the worft is, the Doctor’s Skill does not eafily remove it.

Silicosis

Although lead poisoning was common, lung disease was even

more widespread. If you were a lead miner at Halkyn Mountain

before 1900 you were likely to have died 15-20 years earlier

than the avearage non-miner. This was due to a combination

of silicosis and lead poisoning. Amongst miners, silicosis

was known as consumption, phthsis, miners rot or miners

asthma. It was the earliest known industrial occupational

disease. Records exist of its occurrence at stone mines in

southern England as long as 5000 years ago. It was

eventually identified as being silicosis, caused by silica

dust entering the lungs.

The link beween the disease and dust was made as early as

1556 by the German physician and mining expert Georgious

Agricola, but it was not for another 350 years that his

theories were confirmed. The incidences of silicosis varied

according to the type of rock being mined. For example, the

limestone of Halkyn Mountain did not contain as much

‘free-silica’ as the local chert rocks or the slate mines of

Ffestiniog where death rates were even higher.

When compressed air drills became widely used after 1875,

there followed a huge increase in silicosis deaths due to

the increased amount of dust created. Drilling was carried

out without any method of suppressing the dust. Miners were

soon dying within 3 or 4 years of using these drills without

water. When these drills were first introduced, part of the

equipment that was considered absolutely nesessary by the

manufacturers was a piped water supply “to

cool the bit and damp down the dust”. This was

invariably ignored!

Although the cause is now well established, the mining

industry were very slow to accept that dust was the cause.

In fact it was not until 1904 that the excessive death rate

was officially established as being “due

solely to the inhalation of stone dust”. Drilling

machines were then modified to ensure that a water spray

kept dust to acceptable levels. During the 20th century,

most lead mining at Halkyn Mountain was carried out between

1918 and 1950. During this period most drilling was carried

out safely.

Miners in the nearby collieries did not normally suffer from silicosis due to the low levels of silica in coal seams, although they did however suffer from another lung disease, pneumoconiosis. Although this was also a serious lung disease, colliers nonetheless lived considerably longer than lead miners.

Lead poisoning and Silicosis were common amongst Halkyn

Mountain’s lead miners as the following descriptive quotes

indicate:

“These diseases are

felt in a painful degree as early as the age of 25 and they

gradually increase between this age and 35. They terminate

in a comparatively early death.” (A

local doctor, 1842).

“A pallid earthy

complexion, sunken eyes and such extreme emancipation that

the skin sometimes appears to be pasted to the bones of the

face. The symptoms are harbingers of a chronic incurable

consumption” (1830).

“Those who have

long worked in the mines have a prematurely old appearance,

a stooping gait, and an anxious expression of countenance.

They are thin pale and sallow, and have peculiarly dingy

complexions. The men often have the appearance of being

thoroughly worn out and decrepit” (1864).

“I see colliers who

are old, but I cannot find an old (lead) miner”. (Mold

Coroner Peter Parry, 1864).

“I have seen men

that I would say were not fit to crawl out of bed or over

the door, still going to their work and doing a days

labour” (Mold surgeon Robert Parry 1864).

When a miner gets up about 40 years of age he is not worth the snap of a finger.” (Welsh mine captain, 1864).

Accidents

Fatalities underground, at least in the latter years of the

industry, were not as high as one might expect. In the 40

years from 1873 there were 22 deaths in the mines of Halkyn

Mountain. Typical causes were falling rock, blasting,

falling from ladders or falling down shafts. A young lad at

Rhosesmor in 1860 was climbing the ladders one lunch-time

when, just two yards from the surface, he fell down the

shaft and was killed.

The worst recorded accident in a local lead mine was in 1862

at Bryn Gwiog Mine, near Moel-y-Crio. Miners broke into old

flooded workings and 16 were killed. Their ages ranged from

14 to 66. Seventeen men were working at the ‘120 yard level’

when water burst through from old workings on the same vein.

The flood killed sixteen but Edward Powell was able to find

a ladder and hauled himself up a guide rope to safety. The

accident left 10 widows and 25 children. At a meeting, the

Marquis of Westminster opened a fund with £100 and the

Bryngwiog Mine Company gave £200. By the end of the meeting

the fund had risen to £700. At a subsequent enquiry the

company was cleared of guilt as no mine plans of the old

workings were available to the company.

In 1867, four miners were killed at Deep Level Mine, Halkyn when a collapse was followed by an inrush of water. Those killed were named as John Martin aged 42, Thomas Evans aged 31, George Jones aged 35 and George Hayes aged 21.

Further accidents are described in reports by Mines

Inspectors:

1877 September 5th. Halkyn Deep Level Mine. Thomas Harris, aged 54, miner. The stone lining of a shaft which the deceased and others were sinking came down on him (The Duke of Westminster sent the man’s widow £10).

1886 September 13th. Halkyn Mine. William Jones, aged 26, blacksmith. A large underground cavern had been discovered at Halkyn Mine and the agent made use of a small boat to explore it. After he went away, a blacksmith, who I am told, had never been in a boat before, jumped in out of pure curiosity, and when a little way from the shore of the underground pond foolishly stood up in his frail craft, which capsized and he was drowned. He had married at Halkyn three years earlier and left three daughters. This account describes the cavern when it was first discovered in Powell’s Lode beneath Rhosesmor at a height of about 60 metres above sea level. The full depth of the lake was not realised until 45 years later when the cavern was again broken into at sea level. Even then, the depth of the lake extended at least another 60 metres below sea level.

1896: East Halkyn

Mine. Isaac Stealey aged 24. Was killed when his head struck

against the roof as he was being drawn up seated on a wagon.

He was riding in contravention of orders.

1899: East Halkyn

Mine. Richard Edwards, aged 50, timberman. While repairing

an inclined shaft, he somehow fell to the bottom, a distance

of 25 yards. Killed on the spot.

The above two accidents appear to refer to a shaft just west of Rhosesmor Vicarage. It was called a Plim Shaft which carried men to surface in metal skips. It was closed down due to instability a few years later.

Accidents during the early years were fairly frequent as a result of either primitive practices or carelessness. Many were due to falls of ground or collapses. Conditions improved very little until the mid 1800s when several Royal Commissions were set up to look into the state of the industry. One such commission enquired about Children in Mines in 1842. As part of this enquiry, deaths in mines were studied and amongst the names are local children who died underground….... · Francis Carrington, aged 13. Died at Halkyn (Deep Level) Mine. · William Lloyd, aged 13. Died at Halkyn (Deep Level) Mine. · Joseph Davies, aged 13. Died at Halkyn (Deep Level) Mine. · John Evans, aged 10. Died at Hendre Mine.

Strikes & Unrest

1623: The ancient Mining Laws were abolished by Richard Grosvenor. As already mentioned, a court case followed which resulted in victory for the Grosvenors and the mining laws were extinguished. The ordinary miner would have had poor legal representation in the face of the Grosvenor family who, even then, were both wealthy and influential. Although much bitterness was caused at this time, no records exist of strikes or other action being taken by miners relating to the old mining laws.

1822: Whilst mining was carried out by small groups of individuals, miners were their own masters. But with the arrival of mining companies, relationships between managers and miners could at times deteriorate. By 1822 the Grosvenors mines at Pant-y-go had been in difficulty. They called in John Taylor, the well-known Cornish mining engineer to attempt to improve matters. Taylor brought in other Cornish mine captains and enforced strict new rules for miners. These rules were seen by the miners as unfair and impossible to comply with. A particular complaint against the company was that insufficient timber was being supplied for shoring. The miners wrote a petition which was sent to Parliament which mentions the following: “Respecting Thomas Williams the Underground Agent, he has refused us with a proper supply of timber and we could mention several instances where the miners lives have been endangered by it and your lordship has suffered an unnecessary loss by the works not being properly timbered…….. and if we complain, instead of a redress we have a volley of curses”.

1850: The most bitter disputes were over attempts to change the long-standing 6 hour day to one of 8 hours. The men were well aware of the problems of lead poisoning and chest disease, and considered 6 hours to be more than enough, particularly in mines with poor ventilation as at Pant-y-go. Some Flintshire mines had already introduced 8 hour days by 1850, but when Taylor tried to introduce it at Pant-y-go Mine, he met with strong opposition. A group of 500 miners ransacked managers houses whilst local police were powerless to act. The following week troops were called in and ringleaders were arrested for riot, but no-one would give evidence against them.

1866: “Taylor & Sons” purchased the lease on

Pant-y-go mine and again tried to introduce the 8 hour day.

This also led to several hundred men marching to Pant-y-go

and calling a strike. One week later a detatchment of the

86th Regiment arrived to regain control together with

constables with drawn cutlasses. The Mine Agent addressed

the crowd which then went home without further incident.

Miners claimed that an 8 hour day would double the already

poor mortality rate, but Taylor claimed that nearly all

local mines were losing money and they could not afford a 6

hour day. He also claimed “Miners

were old at 40 due to the extra work they did, not as

workers in my mine”. The miners were however,

able to demonstrate that only 18 of 388 miners actually

worked their own mines.

The strike lasted 12 months during which miners suffered

badly. A handful of non-miners were taken on by the company

and there was further direct action by the miners: A 2 cwt

boulder was thrown down the shaft causing considerable

damage; Eight men working at the mine were seized, roped

together and marched through Holywell and Greenfield.

Eventually the police took action. Armed with sledge hammers and crow bars, they broke into the houses of the ring-leaders and arrested them. They were charged with riot and assault at a special Magistrates Court in Mold. The miners were marched through a crowd of 2,000 to 3,000. One of the men arrested was William Jones from Windmill. He was given six months with hard labour. As a result, his 12 year old son Llewelyn had to leave school to began work as a quarry labourer to keep his family. He died seven years later aged 19. The strike ended when the men eventually gave in and accepted the 8 hour day. Opposition continued however and the following year several hundred men demanded a return to 6 hours due to such wet unventilated conditions in the mine.

1890: The arrival of the Halkyn Tunnel to the area had led to extraordinary profits for many mines throughout the 1880s. In 1890 miners went on strike demanding a share of this wealth requesting an increase in pay of 30%. They went back to work after a few weeks with a 10% rise.

1901: Mining began a serious decline due to a slump in ore prices and miners were asked to take a cut in wages of 10% despite the huge profits the previous year. They went on strike and again miners suffered severe hardship. The Duke of Westminster gave firewood and 700 rabbits whilst a soup kitchen was set up at Rhes-y-cae. Two months later, ore prices had dropped further and the men returned to work accepting the 10% reduction. The decline resulted in the closure of most mines.

1934: The last strike occurred when Halkyn District United Mines attempted to move its centre of operations from Pen-y-Bryn shaft at Halkyn to Olwyn Goch shaft at Hendre. This move could not be avoided by the company which was driving the Milwr Tunnel to the south. The mine manager J.B.Richardson told the men “You can stay out as long as you like; I have bread forever”.The men eventually returned to work for one shilling a day less than before the strike.

In the Miners Own Words

A Royal Commission of 1842 enquired into children's

employment in mines. It provides an insight into the life of

the lead miner on Halkyn Mountain. The following are

extracts of interviews with local people at the enquiry……

James Jones, 17, Milwr Lead Mine Began aged 11 as an ore washer on the surface. Works from 7am until 6pm with an hour for lunch. “The work often binds my bowels” he says referring to lead poisoning. “Our hands are constantly immersed in water and our feet are generally wet while at work”. Paid 7/- a week.

Richard Hughes, 10, Milwr Lead Mine Began aged 9, he gets 3/- a week and gives it all to his mother. The work tires him a little but he is never beaten and he sleeps well. Walks a mile to work. Goes to chapel regularly. “The overlooker makes us work very hard and he won’t let us be idle”.

Owen Owens, Minister, Rhes-y-Cae “The miners are not long livers; they are subject to asthma (silicosis) and they often die early. It is a rare thing to see a miner of the age of 60”.

Edward Redfern, 15, Deep Level Mine, Halkyn Began aged 10 as an ore washer. At 15 his wage was 3/- a week. He could read Welsh and was learning to write. His father was a miner but broke his leg in the mine 5 years earlier and has done no work since. The father was given 3/- a week from the parish. Edward describes his clothes as “Not very good. But I have two suits. My house is not very well furnished. We have a clock and two beds, and good bed-clothes”. Was taught at Lord Grosvenors School.

John Jones, 16, Deep Level Mine, Halkyn Had been dressing ore for six years and was paid about 6/- a week. He was paid 2d a month to pay the doctor and he could read and write. He lives with his mother. His father was killed in the mine 13 years previously. He also lives with a brother and sister. The family lived on the wages of the two boys which totalled 10/- a week. They have a crop of potatoes which occupies their spare time in the Summer. “In the Winter I reads the bible often, help my mother and go to chapel three times every Sunday”. Was taught at Lord Grosvenors School.

Thomas Williams, aged 46 Deep Level Mine, Halkyn Six boys from 10 upwards, worked underground pumping in air to the mine for ventilation. Regarding silicosis “Many miners are carried off before they are 50”.

Edward Roberts, 49, Agent for Hendre Lead Mine “The average pay was 15/- a week for the pitmen and 12/- a week for the borers and drivers. Borers had a more responsible job and attend the mine on Sundays in case anything should go wrong with the engine and the pumps”. Most miners worked a six hour day at this time. In their spare time some miners were self-employed searching for ore. “Two or three or more miners will get a take-note from a proprietor of land, and sink in search of ore. These ventures are seldom successful. I remember miners when they used to be little at home, when they were noisy, always quarrelling and fighting, and committing depredations of all sorts; when the Sabbath was a day of riot and drunkenness. Things are now much altered – they are orderley, well dressed, attentive to their duties and the Sabbath is well kept. This improvement is because chapels have been built in every place”.

Captain Francis Evans, Bryn Gwiog Mine, Moel-y-Crio “There was a custom amongst the miners that no matter what family they had, they would only give their wives 12s a week and no more. If they earned 15s a week they would pay their wife 12s and drink the rest. Farm labourers, if married, are allowed the privelege of a cow. They live a great deal better than miners”.

John Evans, aged 10, Hendre Lead Mine “My father is a gamekeeper but he does not live with us at home. I do not go regularly to chapel as I have very poor clothes and am ashamed of going. My mother requires all my earnings to pay for my food and won’t give me clothes when I require them. Mother goes to chapel regularly but tells me to stay at home when my clothes are ragged. I say the Lord’s Prayer every night and have plenty of food – bread, meat and potatoes, and bread and milk”.

James Pickering, 41 Schoolmaster at Lord Westminster’s charity school, Halkyn “The children pay 1 shilling entrance and 1 penny a month towards fire. Some pay more if they can afford it. Lady Westminster visits and takes great interest in the education of the children. My salary is £70 a year with a rent-free house. We have about 150 children attending the school, but the boys might leave after two years to work in the mines. Most can read pretty well and write by then and they continue to attend Sunday school to keep up their knowledge”.

George Hughes, Mining Agent for Marquis of Westminster “We issue annual grants renewable every year on the first Monday in May. But we have very few of these smaller grants now. They are swallowed up in a great measure by the larger companies, for which leases are granted for periods of 21 years”. “In the smaller workings the men start from the surface. They work down from 5 and 6 down to 20, 30 and 40 yards down; if they get anything which makes it worthwhile, they go down after it. Rhosesmor is an exception, because they did not find the lead ore there till they got to 80 yards deep”. “It is our rule to let an area of 60 yards by 30 yards to two men. Once granted, they can renew it each year. We never take it from them as long as they wish to work it”. The two men work underground until they have an accumulation of ore and then they usually get assistance to raise it. The men then dress the ore themselves and prepare it for the market”. “It is these small ventures that are the worst ventilated, where perhaps 4 or 6 men are working on their own. There was an instance here the other day; Two men were working in the bottom of a shaft but the air was very bad, so that they could hardly breathe., but they had heard from somebody that if they had a stove in the shaft it would cause a better ventilation. They took a stove down to the bottom of the shaft, and of course it had not been there above three or four minutes before they both fell senseless at the bottom of the pit”. “The miner works for 6 hours”. The Grosvenor family tried introducing an 8 hour day but “There has been a great strike about the overworking in our district; they will only work for 6 hours. In other places I find that they work for 8 hours. The 6 hours includes the changing and embraces the going down and coming up as well”. “Some miners have a piece of land attached to their cottages. A great many have stolen a bit of the common from time to time, and they keep a cow. The common is of great assistance in keeping a cow, they make use of the piece they have taken (perhaps an acre or two) for the purpose of getting grass for the cow in the winter, and in the fine part of the year they turn the cow upon the open common for which they pay nothing”. “We cover many abandoned shafts every year. We covered the whole of them over a short time ago, but the boys about there take delight in knocking them down, and it is fine fun for them”.

George Boden, 34, manager of Long Rake Mine near Rhes-y-Cae He employed 26 men at Long Rake in 1841 with no boys or females. “My workers are generally poor, the average wage being 12/- a week. There may be a son or two in each family earning up to 7/- a week. These wages together with a crop of potatoes, which almost every family has, together with what they can make by keeping a few sheep and an ass on the waste or common, allow them to live tolerably comfortable. Some however are very poor and out of employ”. “Many miners join Temperance Societies and there is a vast deal less drinking than there was even two years ago. There are two public houses in the neighbourhood, but I think they might close, they get but little business. After work I see them cutting turf for fire, gathering manure, planting or hoeing potatoes. There are not many idlers and I think them well-conducted, steady people, and bear poverty and hardship without much grumbling. They are certainly more hardy than the English and live more temperately. Miners are affected with compaints of the chest. Many are affected as early in life as 26. They generally die of asthma and few live to the age of 50 if they continue to work in the mines”.

.............................................................................................................................................

Surface interpretation

A book

published in 2004 covers several areas of north-east Wales

and identifies key surface remains. Published by the Council

for British Archaeology, its title is "Mountains & Orefields:

Metal Mining Landscapes of Mid and North-East Wales".

The areas

covered in Flintshire & Denbighshire are:

Halkyn

Mountain

Belgrave,

Eryrys

Eisteddfod, Minera

Lower

Park, Minera

Pool

Park, Minera

Talargoch,

Dyserth

The book

includes detailed surface plans of each area together

with several aerial photographs and is a good source of

surface information. It identifies many features such as

leats, washing floors, whim shafts etc. It does not however

describe the underground workings and no veins are shown on

the surface plans. This omission makes interpretation of

the relationship between veins and surface remains virtually

impossible. A lack of underground knowledge is evidenced by

the erroneous use of the term 'bell pits' in

describing exploratory shafts.

Whilst

several other books describe specific lead veins of the area

(Minera, Talargoch etc), none provide a thorough description

of lead mining in Flintshire incorporating the underground

record. This may be due to the complexity and large number

of veins and the lack of documentary evidence for many of

them, but there is great scope for anyone considering such a

publication.

Acknowledgements

Sources used in compiling the above information are detailed under "Further reading" (see navigation bar on left of page), but particular credit is due to Chris Williams and Bryn Ellis for the use of material, with permission, from their publications shown below: ELLIS, BRYN (1998) 'History of Halkyn Mountain' ISBN 0 9534011 0 3

WILLIAMS,

C.J. (1994) 'Mining Laws of Flintshire and Denbighshire' in

'Mining Before Powder': PDMS Bulletin Vol 12, No. 3.

|