Navigation......................................

01.

Home

02.

General Lead Mining History

03a. Halkyn Mines: History

03b. Halkyn Mines: A few artefact photos

03c.

Halkyn Mines: info downloads

03d.

Halkyn Mines: Don Richardson - electrician

03e. Milwr Tunnel: Recent work

04.

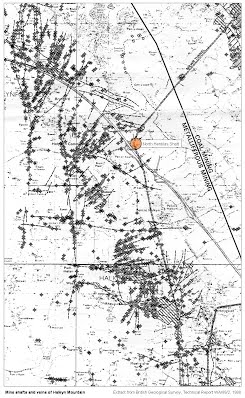

MAP: Veins of Halkyn Mountain

05. Blaen-y-nant vein, Eryrys

06. Westminster vein, Eryrys

07. Fron Fownog Flats, Gwernaffield

08.

Pilkington's vein, Loggerheads

09.

North Henblas Mine, Milwr

10.

Deterioration of the mining record

11. Talargoch Mine

A.

Mines lighting old & new

B. Links

C. Further reading

D. Cris's Shop Window

09. North Henblas Mine, Milwr

Introduction

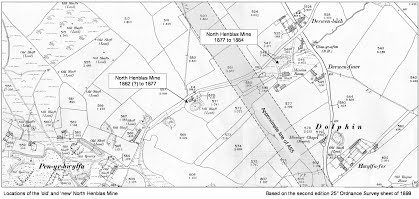

This page describes a disused lead mine site that once occupied land to the west of the Glan-yr-Afon Inn at the hamlet of Dolphin, a mile south of Holywell. The field contains a single deep mine shaft originally described simply as ‘new engine shaft’, but which later became known as North Henblas Shaft. It was sunk to intersect lead ore deposits along the half kilometre long Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein, the eastern end of which terminates beneath the Glan-yr-Afon Inn. At its western end, the vein terminates near Pen-yr-Hwylfa Farm where the vein was worked by North Henblas Mining Company, so-called to differentiate it from the 1850s Henblas Mine, some 600 metres to the south.

The information here is the result of

research by this writer that formed part of a study funded by Cadwyn

Clwyd. I'm very grateful for their consent to reproduce it (somewhat

amended) on this web-site.

Working within the constraints of the brief, documentary evidence specifically relating to North Henblas Mine was found to be sparce. The full story is therefore incomplete.

Click on image to enlarge (then BACK button to

continue)

1 Geological notes

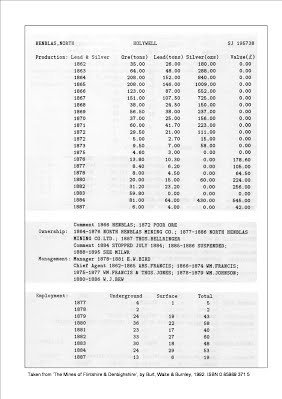

Lead ore (galena) was the predominant mineral found at Halkyn Mountain. Zinc ore (blende) was also worked to a large extent after the invention of the galvanising process in 1837, although no production figures for this mineral were provided by North Henblas Mine. Silver was a by-product of galena found in small amounts of up to 18 ounces per ton at Halkyn Mountain and small quantities were produced at North Henblas Mine.

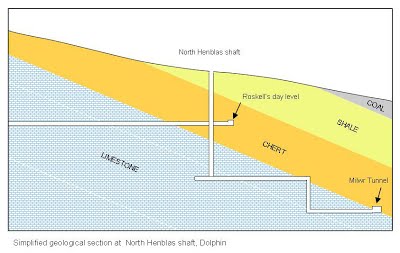

The majority of ore deposits (lodes, veins, rakes, pipes or flats) of Halkyn Mountain were formed in cracks or fissures in carboniferous limestones and, on the eastern boundaries overlooking the Dee Estuary, in overlying cherts. At the time of deposition, molten ores rose up through these brittle and fractured rocks, until their upward progress was halted by the more flexible, and therefore unfractured, shale measures. Furthermore, the mountain strata has been ‘tipped’ downwards to the east. Consequently at North Henblas Mine, ore deposits were followed east through limestones and then into cherts; the vein terminating upon encountering shale measures where the vein lay at its deepest.

Unlike most mines of Halkyn Mountain, the Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein (being worked by North Henblas Mining Company), did not outcrop along the surface at any point. The shallowest deposits lay at its western end where they were 240 feet below the surface. The vein was therefore probably first recognised by miners working at depth in Pant-y-Pydew (or Caeau) vein, which passes Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein at its western end, beneath the property known as Pen-yr-Hwylfa.

Miners working lead veins in limestone rarely if ever, encountered noxious gases, but at the eastern chert-shale boundary, shales (described as being ‘a sulphurous rock’), brought in flammable gases. An explosion occurred in the Beili Gwyn vein half a mile north of Dolphin (Smith Pg 126) whilst being worked from the Milwr Tunnel around 1903 in similar strata.

Chert is a pure form of silica. As a result, miners drilling through chert rock at North Henblas Mine were more likely to have contracted silicosis than miners working only in limestone. The problem was virtually eradicated by the introduction of wet drilling which was adopted throughout the industry, but not until 1904, after the closure of North Henblas Mine.

North Henblas Mine was typical of many mines working the eastern limestone-chert boundary of Halkyn Mountain. Because the deposits tended to lie deeper than those to the west, they were generally worked during the latter period of the industry’s history. North Henblas Mine was not however, as rich as many similar mines and had a comparatively short life of probably 21 years (but certainly no longer than 60), of which the work based at North Henblas Shaft kept the company busy for just 7 years.

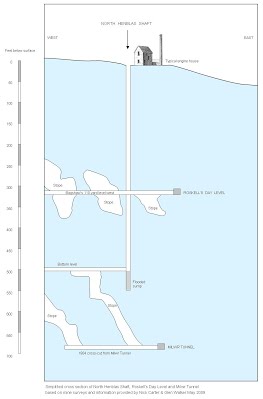

Strata intersected by North Henblas Shaft:

2 North Henblas Mine: Old site west of A55 (NGR: SJ 192 737)

North Henblas Mine worked a lead ore deposit running approximately east-west, known as Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein. A detailed map of the area (FRO:D/GR/1705) shows no shafts or workings along the entire line of the Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein in 1825. In 1845 it became a requirement for all mines to furnish annual production figures. The earliest recorded production figures for North Henblas Mine however, date from 1862. At this time the mine was based around a shaft that now lies just on the western side of the A55 expressway (25” OS map 1869). Ore was worked from a depth of about 240 feet below the surface at this location (Smith 1921). Several shafts were sunk along the line of the vein, all of which are likely to have been of similar depth.

“The belt of ground between the Caleb Bell cross-course and the Lower Coal Measures includes the richest part of the mineral tract of Halkyn Mountain” (Smith 1921, Pg 63). This large area on the eastern side of the mountain includes North Henblas Mine, Caeau Mine, Milwr Mine and many others. Despite the promising statement by Smith, this western part of North Henblas Mine only produced a total of about 1000 tons of lead ore and 4500 ounces of silver. The highest recorded output was in 1865 when around 200 tons of ore and 1000 ounces of silver were produced in the one year. This is a reasonable figure fairly typical of the mines around Holywell at the time, but small when compared with the annual figures of those such as Maeshafn Mine (1000-2000 tons) and Minera Mine (5000-6000 tons).

By the end of the 1870s the vein at this location appears to have been worked out, or become flooded.

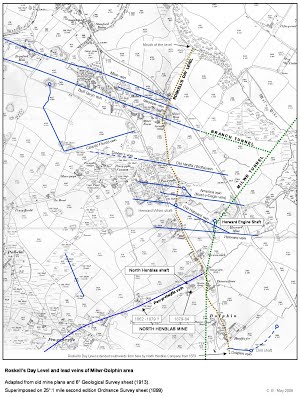

The chief agent (overall manager) from 1866 until 1877 was William Francis of the famous and well respected mining family. After this time Francis left North Henblas Mine to follow his interest in other mines of the neighbourhood. The above survey is produced with the permission of the British Geological Survey (Sept 2009). All rights Reserved. Based upon BGS Technical Report No: WA/88/2. Please refer to BGS Terms and Conditions if reproduction is required: http://www.bgs.ac.uk/about/copyright/non_commercial_use.html

3 North Henblas Mine ‘New’ site east of A55 (NGR: SJ 1947 7376)

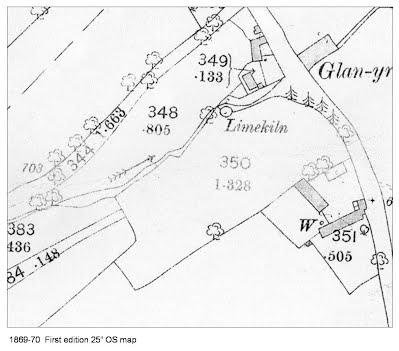

In order to reach deeper potential deposits on the same vein, the company moved its operations 200 metres eastwards to a field behind the Glan-yr-Afon Inn after becoming a limited company in 1877. At this new location, William Johnson was chief agent until 1879, after which W.J. Bew took over the running of the mine.

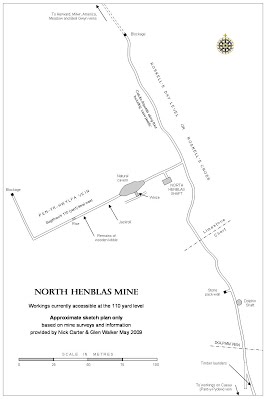

The company cost-book (FRO: D/DM/186/10) describes in its opening pages: “Sinking new engine shaft”. This later became known as North Henblas Shaft, which first reached ore-bearing ground at a depth of about 330 feet in 1879. It reached its total depth of 535 feet below the surface in 1881.

The shaft cross-section at its top measures 2.4m x 4 metres (8ft x 13ft); a large shaft when compared with most in the area, although three or four others of similar size are known to exist elsewhere on the mountain. A timber ‘ladder-way’ was constructed down the south-west side of the shaft. Although the ladder-way no longer remains, it is evidenced by the existence of ‘bunton hitches’ (locating holes for platform timbers) extending down the length of the shaft. It seems likely that such a large shaft was sunk in expectation of finding rich deposits at this end of the vein. The limited extent of workings however, and the low production figures, suggest optimism was misplaced. Passages were driven off the shaft at depths of around 330 feet and at 500 feet (just above shaft bottom) and ore was found, but not in any large quantities.

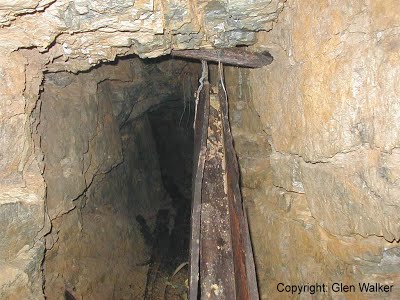

Another view down North

Henblas Shaft

Photo: Glen Walker

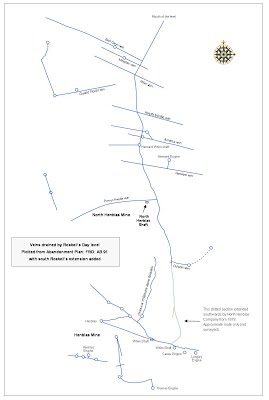

North Henblas Mining Company Limited produced ore at North Henblas Shaft from 1879 until 1884. During this five year period several ‘runs’ of ore were exploited within Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein. The nearby Roskell’s Day Level (details below) was cleared out and repaired and the company also extended this level southwards to where it was eventually connected to workings on Pant-y-Pydew (or Caeau) vein. Although some further ore deposits were found along Roskell’s Day Level, the mine lay idle after April 1884. A final effort to find ore at this site occurred in 1887 when 19 were employed at the mine (13 underground and 6 at surface) and a total of just 6 tons of ore were produced.

In 1888, the company was re-launched as Milwr Mining Company Limited under the same manager as at North Henblas; Mr W. J. Bew. The new company worked several nearby veins (most of which had been idle for 20 or 30 years) and continued to make entries in the same cost-book used by the North Henblas Mining Co. Ltd., although no further mention is made of work on Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein after 1884.

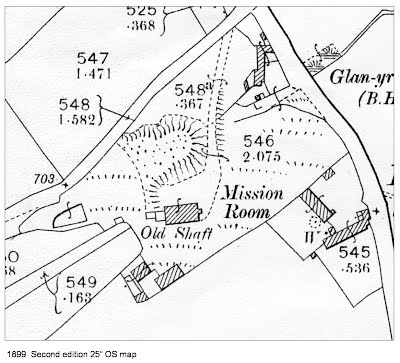

Some time between 1888 and 1899 the mine buildings at North Henblas Shaft were removed, leaving only the old engine house which was being used as a ‘mission room’ in 1899 (Second edition 25”:1mile Ordnance Survey map). It's clear from the OS map above that no development had taken place on the site by 1869 By 1899 a milling complex had been erected on the site and then demolished after just seven years in operation. The disused engine house was then used as a Mission Room In 1897 Milwr Mining Company Limited became part of the Holywell-Halkyn Mining & Tunnel Company who began driving the Milwr Tunnel from the coast at Bagillt, reaching Herward Mine in 1903. This tunnel drained the North Henblas Mine to sea level in 1904 when Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein was identified at sea level in the Milwr Tunnel and a passage here was driven along the vein for 48 yards. A little ore was found at this depth and a rise was then driven upwards for 150 feet to the bottom of the old workings at North Henblas Shaft. At this time, ore was carried in tubs drawn by ponies to the dressing floors at the portal of the Milwr Tunnel at Bagillt, each pony hauling out 25 tons a day. After this period, the Milwr Tunnel continued its route southwards and Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein was never worked again.

It was hoped that early records might still be held at Companies House, London. Checks have been carried out for North Henblas Mining Company and North Henblas Mining Company Limited, but no records under these names now exist.

Roskells’ Day Level

Drainage of the ‘new’ eastern site at North Henblas Shaft was effected by pumping to surface until the shaft reached the depth of 330 feet where a connection was made to the old ‘Roskell’s Day Level’. This tunnel was originally commenced in 1754 from a point nearly two miles to the north. The first lease for the tunnel was granted by the Pennant family in 1754. The lessees aim was to reach Hard Shaft (on Herward vein), but the level had not reached this point by 1796 (Pennant Pg 255). Rich veins were found however, before this point providing over £100,000 to lessees and lessors (Pennant Pg 256).

The level ultimately drained the neighbouring lead veins of Milwr, Herward, Beili Gwyn, Meadow, America, Pen-yr-Hwylfa and Dolphin creating an inter-connected network of passages exceeding 6 miles in length. An old map of Roskell’s Day Level describes Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein as “A beautiful vein composed of sugar spar etc two feet wide” (FRO: D/GR/1799). North Henblas Mining Co. Ltd. refurbished and repaired the old drainage level which also allowed the company to prospect for ore in the areas to the north (Herward and Milwr Mines) and to the south (Caeau and Henblas Mines). Sinking North Henblas Shaft

It seems that work on sinking the shaft began in 1877. Compressed air for drilling was a new innovation at this time and was likely to have been used by the drillers in sinking the shaft. Although compressed air permitted significantly faster drilling than manual methods, water was not used to dampen down the resulting clouds of dust. Hence when drilling through cherts at the bottom section of the shaft, as already mentioned, miners will have significantly increased their chances of acquiring lung disease in the form of silicosis.

The method adopted probably involved a team of 4 or 5 men working in the shaft. Work would have included the frequent re-positioning of the pumps: raising (before blasting) and lowering (as the shaft became deeper); drilling shot-holes and setting charges. After drilling a ‘round’ of perhaps 20 shot-holes, each would be ‘charged’ (filled) with high explosives and a detonator. Wires from each of the detonators would be connected together and wired to an exploder on the surface. Drilling would re-commence after the poisonous fumes had cleared.

Water would have entered the shaft in the form of heavy rain, particularly as the shaft became deeper, and the team will have worn waterproofs whilst working. Some protection may have been provided by sheeting fixed above the top of the lowered shaft cage. On the surface, a steam engine initially operated a 14” lift pump to keep the shaft ‘dry’. Another steam-operated winding engine operated a cage in the shaft for lowering men. The cage may also have been used for raising wagons loaded with waste rock. A steam capstan winch was also used at North Henblas for installing heavy machinery and pump rods. By 1879, the shaft had reached the depth of Roskell’s Day Level (330 feet below surface), and levels were being mined east and west along Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein. The pumping arrangement would have been altered at this depth to discharge all water into Roskell’s Day Level instead of raising it to surface; water in the Day Level running north by gravity and discharging into a brook south of Holywell. In October 1879, the shaft sinking team again continued sinking downwards at a cost to the company of £6 per yard depth. The team finished sinking in June 1881 at the final depth of 535 feet below surface and were mining to the east and west along the vein about 30 feet above shaft bottom. It seems that mining at the deepest levels was severely troubled by water: The 14” lift pump struggled to cope and in November 1882 an additional 7” hose lift pump was installed. This proved ineffective and in May 1883 a larger engine was installed in the engine house and the following three months were spent installing an additional 24” lift pump.

By early 1884 mining was still hampered by water: Records suggest that a large Cornish engine was about to be installed. In February of that year, masons strengthened the engine-house wall and 23 men manoeuvered a huge cast-iron beam into place ready for the new engine. It appears however that the Cornish engine may never have been fitted as there is no mention of its installation in the cost-book and the mine closed down just four months later in June 1884. The mines’ sudden closure was probably due to a combination of high pumping costs and low production figures at a time of falling ore prices.

Production figures

The vein at North Henblas Shaft (east of the A55) was not very productive. Mineral statistics indicate that only about 200 tons of lead ore and 500 ounces of silver were produced in total (about a fifth of that produced at the west end of the vein, west of the A55). Production figures for North Henblas Mining Co. Ltd. held by the Grosvenor family (upon which royalties were calculated at 20 shillings per ton) are even lower. This could suggest an unwillingness by the company to reveal actual output in order to reduce their costs. Conversely, it could also suggest a degree of leniency on the part of the Grosvenors in a difficult mining climate. 4 The Mill at North Henblas Shaft

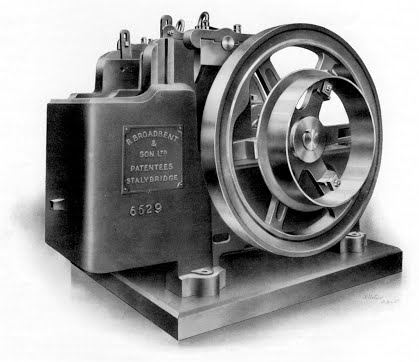

Ore dressing

Ore mixed with waste rock

and mud was raised and processed at North Henblas Shaft. The processing

operation known as ‘ore dressing’ simply involved the separation of

waste rock from valuable ore. Ore dressing in the 1870s was to a large

extent, carried out by machines, particularly at the larger mines. Some

smaller mines however, still used manual labour for most operations.

Although no documentary evidence has been found describing the methods

used at North Henblas Mine, it seems quite possible that ore cleaning,

jigging and buddling were carried out using man- or boy-power, whilst

crushing was achieved by a steam-powered machine such as a 'Blake’s'

stone crusher.

It appears the dressing floors may have been covered to protect workers from rain, as the 1893 sale catalogue (for Milwr Mine) mentions “galvanised shedding on pitchpine supports over dressing floors”.

A Blake's stone crusher,

manufactured by R. Broadbent & Son Ltd. (copied from a 1930s Halkyn

District United Mines catalogue) and typical of the crushers that may have

been in use at North Henblas

The dressing process:

Cleaning Cleaning of the ore/waste mix achieved by agitation in running water.

Jigging After large lumps of pure galena were removed by hand, the mix would be placed into a jig. This is a simple wooden box (approx. 4ft long x 2ft x 2ft deep) shaken by a long rocking handle. By lifting the handle, the box is lowered into a water container. By ‘leaping’ (Ure 1867) up and down on the lever, the box is agitated or ‘jigged’ beneath the water, causing the heavier ore to sink to the bottom and the waste to rise to the top where it can be removed.

Crushing The remaining material then needs to be finely crushed in order to separate ore from waste rock using buddles. In the days before crushing was carried out by machine, teams of workers achieved the same results using bucking hammers; tools having a thick steel plate about 4” x 4” with a handle about 2 feet long.

Buddling The crushed mix was then separated from waste rock in buddles. Although buddles of many different designs have been used at local mines, all buddles use a continuous flow of water to wash the mix down a slightly inclined plane, the lighter waste material being washed further than the ore, therefore becoming separated. Catch pits Waste residue with very small amounts of ore was then carried by water to the ‘slime catch pits’ lower down the field. Here the finest ore pieces settled into large tanks whilst surplus water and waste overflowed and ran off down the valley.

Weighing and transport Clean ore was weighed, packed into barrels and loaded onto horse-drawn carts to be taken away for smelting (the process of using high temperature furnaces to produce pure metallic lead from galena).

Ore from North Henblas was smelted (in 1864) by Newton, Keates & Company at Bagillt, one of three Flintshire smelteries known to have been in operation at the time. The coast here had well-established sea and rail routes provided easy access to World markets. Empty carts would then travel to one of the nearby coastal collieries to load up with coal for the return journey back to the mine.

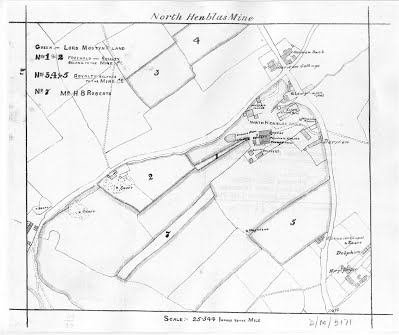

Plan showing the mill at North Henblas Shaft. Although

undated, it is thought to be around 1880 (courtesy of Flintshire Record

Office. FRO: D/M/5171)

Mine equipment

It is not possible to say with certainty exactly what equipment was being used at North Henblas Shaft, however, a prospectus issued by the new Milwr Mining Company in 1888 (chiefly comprising the North Henblas machinery used the previous year), describes the company’s equipment as including a compound pumping engine (comprising a 30” high pressure engine and a 56” low pressure engine, capable of pumping about 1,100 gallons per minute). An 1893 liquidation sale catalogue for Milwr Mine (FRO: D/DM/244/73) describes this engine in more detail, together with ancillary equipment:

“A compound condensing pumping engine, by Hathorn, Davey & Co., 30 and 56 inch cylinders, 8 feet stroke, T bobs and pitchpine main pump rods, with 24 inch, 18 inch and 14 inch lifts; five Lancashire boilers; 18 and 14 inch winding engines; 18 inch air compressor and rock drills, stonebreakers, crushing rolls and modern dressing plant; pit heads and winding gear; a double cylinder portable engine and boilers; a 12 inch capstan engine, steam winches; 2 vertical engines; one 14 inch geared pumping and winding engine; three Cameron pumps; Haywood Tyler pump and pulsometer; donkey pump; tubular boiler; a powerful team of two cart horses” etc etc.

Mine buildings and equipment

The following buildings were erected around North Henblas Shaft as shown on the undated (around 1880) mine plan shown above:

Engine pool: A small stream passing through the site supplied the engine pool. This supplied water for the pumping engines boilers and for cleaning and separating ore at the dressing floors.

Slime catch pits: After crushing and separating of the ore, water carried off the waste material with the smallest ore particles which settled in the ‘slime catch pits’ lower down the field.

Engine house: (Approx. 22ft by 16ft) Housed the steam engine which kept the shaft and workings free from flooding.

Boiler house: (Approx. 28ft by 12ft) A room built onto the north side of the engine house to supply steam power to the main pumping engine and also the capstan and winding engines. It is likely that 26ft long ‘Lancashire boilers’ were installed here.

Changing house: (Approx. 22ft by 5ft) A long narrow room built onto the south side of the engine house for miners to change into work clothes before and after their underground shifts. Fitted with steam pipes from the boilers for drying purposes.

Winder: A steam winch used for raising men and equipment.

Capstan: Mainly used for lowering heavy equipment into place, particularly in shaft work. Possibly the 12” cylinder capstan engine offered for sale in 1893.

Smithy: For sharpening drill steels and manufacturing mining tools and equipment.

Weighing machine: Where ore production figures were recorded.

Stores: Where drill steels, candles, tools etc were sold to miners.

Powder magazine: Where explosives, detonators and fuses were stored. Situated a safe distance away in a field to the south.

Un-named building: The undated mine plan also shows a small building placed behind the smithy and stores. This may have been a miners’ toilet and could be that described in the 1893 sale catalogue as “galvanised iron removable privy”.

5 Miners lives

The hamlets of Dolphin and Milwr grew in size as a direct consequence of local lead mining. The Glan-yr-Afon Inn, being 450 years old will have witnessed the building of new homes to accommodate the growing work-force during the 1700s, particularly after the driving of Roskell’s Day Level (begun 1754) which drained all the Milwr, Herward and Dolphin area veins to a depth of 300 feet below the Glan-yr-Afon Inn.

Based on the company cost-book and the 1881 census, half of the forty-strong workforce lived within about half a mile of the mine, half of those living on the doorstep at Dolphin. Living closest was John Edwards ‘lead miner’ who was living at the Glan-yr-Afon Inn and working at North Henblas Mine where he was earning 3/1d a day as a tunneller on ‘tutwork’ (A system of payment whereby groups of miners contract to work at previously agreed rates, usually for shaft sinking or driving levels).

Next door at Derwen Cottage lodged William James Bew aged 40 “Manager of lead mines”, the manager at North Henblas Mine.

Forty three people lived at Dolphin (cottages?) in 1881, of which nine were miners. Two of those were Isaac Lloyd (47), labouring at the surface, and Evan Evans (56) who worked ‘at the pool cleaning ore’ and also spent time ‘watching’ (a watchman) at the mine. A father and two sons from Milwr worked at North Henblas: Thomas Jones (59) worked on tutwork and in painting boilers, whilst his sons Edward (32) and William (30) were at the pool washing ore, also earning 3/1d a day. It appears that although men at North Henblas Shaft may have specialised in certain mining skills, they were also adaptable and undertook any work required.

The cost-book shows

that in 1881 men and boys were employed underground driving a

level leading off North Henblas Shaft. Documentary evidence of boys

employed underground is uncommon: At the Kinnaird Commission enquiry of

1842, local mine companies claimed that boys only worked on the surface,

usually washing ore.

Although women were

sometimes employed ore washing on the mountain, only men or boys are

recorded as doing so at North Henblas Shaft.

The long and narrow changing room next to the engine-house engine and fitted with hot pipes would have been of great comfort to the men on cold Winter days, particularly those washing ore which may have involved standing in water for much of the day with little protection from the weather except perhaps basic corrugated iron roofing.

Although shaft sinking work was wet and dangerous, conditions for the average underground miner were not too unpleasant. The normal temperature of the workings was around 8 degrees Centigrade and has been described by other Halkyn miners as a good temperature in which to work. Lighting was provided by tallow candles (purchased by each miner from the company store) which burnt with a warm yellow tinge and provided far more light than most modern-day wax candles. Miners wore felt hats with a lump of clay pressed to the front to hold a candle, thus providing hands-free lighting. The matter of health and safety did not of course, receive the attention it does today, each miner being largely responsible for his own safety. A strike did occur however at the Grosvenor’s nearby Pant-y-Go Mine when the company were accused of saving money by cutting down on timber for shoring.

Religion was an important aspect of daily life to the local miner and his family in the 1870s and 80s, and most attended chapel regularly. In a passage below North Henblas Shaft, a Celtic cross has been hammered onto the wall, below which a lump of clay appears to have once held a candle to illuminate the cross, as shown below. 6 Modern day exploration

It appears the site may have been landscaped to some degree after the last mine building was removed. Earth from this work covered and obscured the concrete cap built over the shaft. Following the re-discovery of the shaft by the land-owner, Grosvenor Caving Club became interested in the site and first descended the shaft in April 2002. A year or so later, the United Cavers Exploration Team also began exploration work. Both clubs have a continued interest in the mine workings and further discoveries are regularly being made. The clubs also maintain good relationships with the land-owner.

Initial work by the club included assisting the land-owner to install a new and stronger concrete cap following instructions set out in an engineer’s report. A scaffold platform was then erected beneath the cap to act as a safe point for future descents. Passages along the Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein total just a few hundred metres in length. Consequently, club activity has centred on the workings that lead off Roskell’s Day Level which, to the south, encompass workings of Caeau Mine. To the north, workings are currently being explored in the area of Herward vein. Landing platform 330 feet below surface at the depth of Roskell's Day Level Photo Glen Walker

Roskell's Day

Level

Photo Martin Poole

Artifacts

A sample of the items represented in the explored workings include:

Work today continues in extending Roskell’s Day Level northwards towards its portal, and in exploring the remaining veins drained by Roskell’s. Timber launder originally suspended from passage roof at the south end of Roskell's Day Level Iron kibble for raising ore and waste materials to surface Old jack-roll or turn-tree, part of a hand windlass for winding buckets up an internal 'rise' Back-filled passage off Roskells' Day Level

Roskell's Day Level looking south and showing the dip of

the strata

If any reader has information or photos they'd like to add to this page, please get in touch.

..........................................................................................................................................................................

Supporting information

A Extracts from the company cost-book

List of North Henblas miners 1879-80

Pitman: Peter Griffiths at £5 a month; also John Price with pitman

Miners (on tutwork) at 3/1d a day: John Edwards, Evan Williams, Thomas Jones, Thomas Edwards.

At pool (washing ore) at 3/1d per day: William Bryn (puddler), Thomas Edwards (labourer), Thomas Edwards (labourer), William K. Jones (labourer), Edward Jones (labourer), Evan Evan (labourer), Evan Williams (labourer), John Price (labourer), Charles Williams (labourer), John Jones (boy) at 2/0d a day, Robert Evans (boy) at 2/0d a day

Road making to clay, lifting pumps etc at 3/1d a day: William Bryan, Thomas Edwards

Watching (watchman) at 3/- a day: Evan Evans

Carpenter: Peter Lloyd

Striking in Smithy: Charles Williams

Painting boilers at 3/1d a day: Thomas Jones, Richard Jones

Shaft work: Six day weeks at 3/6 or 3/1d a day

Boys @ 2/- a week: Thomas Evans, Thomas Lloyd, Peter Lloyd, William Pierce.

Mason: William Bryan

Lawyer: Josh Kenrick

Blacksmith: Robert Roberts

Striker: Robert Evans

Also two engineers and two stokers

Company stores

Supplies were issued by the company at their Stores a few yards to the south of North Henblas Shaft (where the property known as Dysgwylfa now stands):

Candles: between 6d and 8d a pound

Powder: between 6d and 8d a pound

Dynamite: 2/1d a pound

Caps (detonators): 4/- per 100

Coils of fuse: 8d per coil Areas being worked:

Work by the company was being carried out at several locations at one time namely, on the Pen-yr-Hwylfa vein itself, extending the old Roskell’s Day Level to the south, and at Herward Mine, 300 metres to the north. The following are typical of the cost-book entries:

August 1879 Three miners driving 110 yard Bagshaw’s level west: One at £1-10-0 per yard, Two at £2-10-0 per yard: Timbering Herward Shaft at 3/1d a day: Painting boilers.

Sept 1879 Opening up Roskell’s Cross: Timbering Herward Shaft.

Oct 1879 Roskell’s Cross: Sinking new engine (North Henblas) shaft.

Nov 1879 Driving 110 west of upper shaft: Driving south vein of Roskell’s: Clearing Roskell’s Cross; Sinking Engine Shaft at £6 a yard.

Dec 1879 Sinking Engine Shaft at £7 a yard: Driving cross-cut from Bagshaw’s 110 west: Driving south vein: Miners in Roskell’s getting lead.

Jan 1880 Sinking Engine Shaft: Driving cross-cut from Bagshaw’s 110 west: Driving south vein off Roskell’s.

Feb 1880 Sinking engine shaft: Driving cross-cut from Bagshaw’s 110 west: Driving south vein off Roskell’s.

March 1880 Sinking engine shaft: Rising in roof of Bagshaw’s.

Sept 10th 1881 Twenty men and boys driving a level west from Engine Shaft

B 1881 Census

Mining families living closest to North Henblas Mine

Glan’rafon John Edwards (head) lead miner Sarah Edwards (wife)

Derwen Cottage William James Bew (40) lodger: Manager of lead mines Edward Jones (57) head: Stoker in lead mines Geeorge Jones (15) son: Stoker in lead mines Thomas Hales (24) lodger: Store-keeper in lead mines

Dolphin (Cottages?) Richard Hughes (38) head: Lead Miner Martha Hughes (340 wife Elizabeth Hughes (24) daughter: General servant Benjamin Jones (26) head: Lead miner Catherine Jones (21) wife Isaac Lloyd (47) head Lead miner Catherine Lloyd (49) wife Elizabeth Phillips (66( head: Miners widow Geoge Kennedy (32) head: Lead miner Evan Evans (56) head: Lead miner Sarah Evans (36) wife Robert Evans (17) son: Labourer Edward Evans (16) son: Labourer Francis Evans (13) son: Labourer James Price (64) head: Lead miner Maria Price (70) wife Ann Nuttall (49) head: Lead miner’s widow John Price (41) head: Lead miner Susannah price (42) wife Most of the remaining 24 living at Dolphin were labourers or employed at local farms.

Pen-yr-Hwylfa (at west end of vein) Robert Bagshaw (41) head: Lead miner (linked to ‘Bagshaw’s 110 yard level’ at North Henblas Shaft?) Hannah Bagshaw (40) wife James Bagshaw (19) son: Lead miner Sarah Bagshaw (12) daughter John Bagshaw (10) son: Scholar Daniel Bagshaw (6) son: Scholar Peter Bagshaw (3) son Llewelyn Bagshaw (1) son Jane Edwards (36) head: Lead miner’s widow Edward Williams (31) head: Lead miner Frances Nuttall (48) head (with his large family): Lead ore miner

The respected mining engineer Henry Vercoe (37) lived a quarter of a mile to the north at Maes Gwyn with his wife and three children. Vercoe was born in Cornwall but moved with his family from Cumberland to work in local mines.

C Main sources

Maps & plans 25”:1mile Ordnance Survey sheets (first & second editions) Geological Survey sheets 6”:1mile (1913 editions). Tithe maps (Holywell & Halkyn parishes) Abandonment Plans AB 88-91 Milwr Mine Abandonment Plans AB 77-79 Herward Mine

Books & articles Pennant: The History of the Parishes of Whiteford & Holywell 1796 Jones, Walters & Frost: Mountains & Orefields 2004 Ellis, Bryn: The History of Halkyn Mountain 1998 Ebbs, Cris: The Milwr Tunnel 2008 Burt, Waite & Burnley: The Mines of Flintshire & Denbighshire (Mineral Statistics) 1992 North, F.J.: Mining for metals in Wales 1962 Lewis, W.: Lead Mining in Wales (FRO) Bevan Evans, M.: Gadlys & Flints Lead Mining in the 18th Century. Flints Hist. Soc Vols 18-20 Ure's Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines 1867

Unpublished thesese Quant, V:. Lead Mining in Clwyd 1963 Rhodes, J.N.: The London Lead Company in Wales 1972

Reports Smith, B. Lead & Zinc Ores in the Carboniferous Rocks of North Wales 1921 Kinaird Commission Report 1842 Strahan, A.: Geology of the neighbourhoods of Flint, Mold and Ruthin. 1890

Internet CPAT Mines Index: http://www.cpat.org.uk/projects/longer/mines/minesidx.htm Archaeological guidelines of the National Association of Mining History Organisations: http://www.namho.org/

Documents and other sources Catalogue of HDUM manuscripts Catalogue of Grosvenor Estate manuscripts Catalogue of Mostyns (Sir Thomas Mostyn) manuscripts Catalogue of Mostyn of Talacre manuscripts Catalogue of Keene & Kelly manuscripts Census Returns 1881 Companies House, London Mining Journals 1871 (pg 697) and 1872 (pg 307) D/DM/186 North Henblas Mine cost-book. 1879 to 1907 D/DM/219/29 Mining reports 1877 – 1905 D/DM/219/30 Engineers reports. D/DM/219/72 Francis Francis, ‘Mining Engineers & Share Broker’. Reports on several mines. 1878 D/DM/224/73 Sale catalogue, mining equipment. Milwr Mine 1893 D/DM/224/14 Milwr Mine cost-book 1880. Each page headed: ‘North Henblas Mine’ D/DM/224/18 Wooden model showing veins at Milwr and Dolphin. D/DM/219/28 Section along Caleb Bell cross-course D/HM/43 Shafts sections onto tunnel D/HM/44 as above D/KK/1558 Indentures & letters 1858: N. Henblas & Queen of the Mountain D/PW/12(g) Map of Dolphin area D/DM/186/10 N. Henblas cost-book 1879-1907 D/DM/244 Collection of papers relating to Milwr Mine D/M/5171 Plan of N. Henblas Mine showing named mine buildings and land ownership. D/M/5186 Herward. Correspondence re trials D/M/5210 Herward. Plan of mining ground at Milwr & Dolphin 1860 D/GR/178 List of mine leases and royalties D/GR/181 List of mine leases and royalties D/GR/294 List of leases & takenotes 1710 to 1881 D/GR/296 List of mine leases 1851 to 1882 D/GR/525 Grosvenor papers showing tonnages from each mine, inc North Henblas D/GR/579 Sale poster (large) 1866. Mine equipment at Billins D/GR/602 Sale poster (small) 1886-7. Mine equipment at Prince Patrick D/GR/1535 Mining Journals D/GR/1543 Mining Journals D/GR/1688 Map of area at Halkyn to north 1799. Copied from Badeslade’s map D/GR/1705 Roskell’s Day Level & Dolphin area 1823 D/GR/1789 Mine section along part of Roskell’s Day level D/GR/1793 Milwr Mines sections 1846 at Milwr D/GR/1799 Roskell’s Day Level and veins. 19th c D/HM/48 6” OS map marked with veins between Holywell and Hendre

Cris Ebbs July 14th 2009

|