Navigation......................................

01.

Home

02.

General Lead Mining History

03a. Halkyn Mines: History

03b. Halkyn Mines: A few artefact photos

03c.

Halkyn Mines: info downloads

03d.

Halkyn Mines: Don Richardson - electrician

03e. Milwr Tunnel: Recent work

04.

MAP: Veins of Halkyn Mountain

05. Blaen-y-nant vein, Eryrys

06. Westminster vein, Eryrys

07. Fron Fownog Flats, Gwernaffield

08.

Pilkington's vein, Loggerheads

09.

North Henblas Mine, Milwr

10.

Deterioration of the mining record

11. Talargoch Mine

A.

Mines lighting old & new

B. Links

C. Further reading

D. Cris's Shop Window

11. Talargoch Mine

Talargoch Mine at Dyserth was one of the oldest metalliferous mines in

Flintshire, likely to have been worked in Roman times.

Clive engine-house in 1974

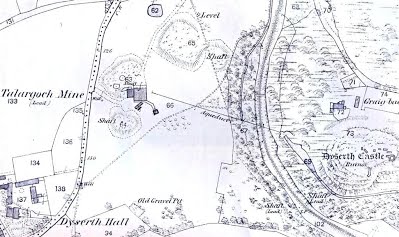

Photo: C. J. Williams The engine-house at Clive Shaft, beside the A547 road between Meliden and Dyserth (NGR SJ 056801), is one of the few remaining buildings associated with the Talargoch lead mine. It is the best-preserved Cornish-type engine-house in Wales. The mine, one of the largest in north-east Wales, was worked from 1632 to 1884, and was at times very productive and profitable. The workings were on three near-vertical veins which ran from the outskirts of Dyserth village to near Meliden church. The main buildings, the last of which was demolished in the 1960s, were below Graig Fawr, to the north of Clive engine-house. The deepest shaft, Mostyn Shaft, was on the east side of the main road, opposite Meliden church, and was over 1,200 feet deep. Ordnance Survey 25-in map 1871

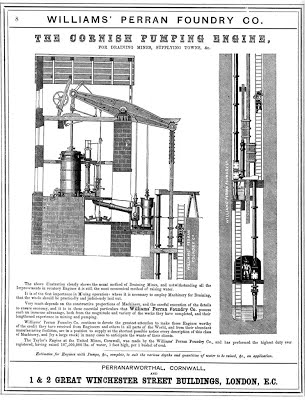

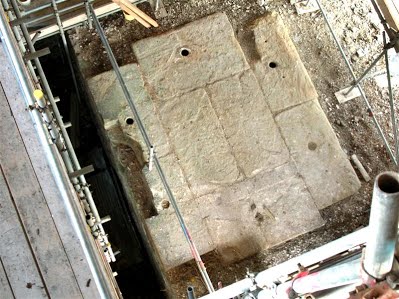

A Cornish pumping engine In the nineteenth century, as shallower workings were exhausted, the mine company spent enormous sums on pumping engines to keep the workings free from water. The Clive Shaft engine-house was erected in 1860 to house the largest of these engines, which was built for £15,000 by the Haigh Foundry, Wigan, and began work in 1862. The engine-house was built by a local man, Thomas Roberts, and his sons. The engine had a 100in cylinder and 10ft stroke, a size equalled at only two other mines in Flintshire – one at Mostyn Colliery (1852), and another at the North Hendre lead mine (1865). Clive was the family name of the Earl of Plymouth, who owned the mineral rights of part of the mine. A party visits the scaffolded engine-house Photo: C. J. Williams Interior during restoration Photo: C. J. Williams Pumping engines of this type consisted of a vertical cylinder on massive foundations. The piston was attached to an iron bob or beam weighing 85 tons, which was mounted on the wall of the engine-house nearest to the shaft. The other end of the bob was linked to a wooden rod connected to a series of pumps in the shaft. The pitwork was balanced so that the engine on its working stroke raised the rod, which fell under its own weight on the exhaust stroke to work the pumps. It worked at about 3½ strokes a minute. Clive Shaft was about 750ft deep, and the pumps raised water up to the day level or adit, about fifty feet below the surface. A gallery projecting from the front of the house allowed the engine-man to inspect the beam. Tall wooden shears over the shaft were used for maintenance of the pitwork.

Engine bed from above

Photo: C. J. Williams Restored roof timbers Photo: C. J. Williams

Restored

roof Photo:

C. J. Williams Coal was brought from Point of Ayr Colliery to raise steam for the engine. There were seven egg-end boilers, 40ft long and 5ft 6in in diameter, in a building on the side of the house away from the road. On the other side was a culvert used to drain the waste water. Clean water for the boilers was supplied by a wooden aqueduct (shown on the Ordnance Survey 25-in map of 1871), which ran about 700ft in an easterly direction to a watercourse built to bring water to the mine. This was fed by the river about a mile east of Dyserth. Graig Fawr, site of early mining, seen from the engine-house Photo: C. J. Williams Restored bob wall Photo by courtesy of Recclesia Ltd

Restored finial at south end Photo by courtesy of Recclesia Ltd When the mine closed in April 1884 the engine was sold, with the rest of the plant and machinery, by auction. The Clive engine was re-erected at Westminster Colliery, Gwersyllt, near Wrexham, where it remained until it was broken up and scrapped in 1925. The original engine-house at Talargoch was abandoned, although unusually the roof was left on it. Standing as it does beside a busy main road, it is a well-known local landmark, and thousands of local people have watched it decay throughout their lives. Interior after restoration Photo by courtesy of Recclesia Ltd Interior after restoration Photo by courtesy of Recclesia Ltd Restored exterior Photo by courtesy of Recclesia Ltd

In 2010 Cadw and Denbighshire County Council together applied for a £100,000 grant to conserve and restore the engine-house from the WREN Heritage Restoration Fund. WREN is a not-for-profit company that awards grants to community, conservation and heritage projects within a ten-mile radius of landfill sites, from funds donated by the Waste Recycling Group to the Landfill Communities Fund. Cadw and Denbighshire County Council also provided part of the funding for the project. Conservation architects Donald Insall Associates were appointed to draw up plans, and the work was carried out by Recclesia Ltd of Sandycroft, building conservation and restoration specialists. A detailed description of the restoration is available on their website at: http://www.recclesia.com/conservation/portfolio/portpages/cliveenginehouse.html

Christopher J Williams

January 2013

Further reading J A Thorburn, The Talargoch Mine (Northern Mine Research Society: British Mining No 31, 1986) C J Williams, Metal Mines of North Wales, 2nd ed (Bridge Books, Wrexham, 1997) D B Barton. The Cornish Beam Engine, New ed (1969) Frank D Woodall, Steam Engines and Waterwheels (Moorland, 1975) J H Trounson, Cornish Engines and the Men who Handled Them, 2nd ed (Trevithick Society, 1992)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Further supporting notes Talargoch was one of the most productive mines in Flintshire. It has produced minerals such as copper, silver and calamine, but it is most famous as a producer of lead ore, and from the 1860s, zinc ore. It is likely to have been worked since Roman times, but the evidence merely suggests, not confirms this. The mine was producing around 400 tons a year in the 1660s but during the mines last 40 years up to 1884. it produced nearly 60,000 tons of lead ore (galena) and 50,000 tons of Zinc ore (blende). Unlike many Flintshire mines during the 1600s and 1700s, Talargoch’s minerals were owned by the landowner (and not by mineral owning families such as the Grosvenors). Its peaks of production occur in the 1850s for lead and around 1880 for zinc. The mine had strikes in 1852, 1856, 1877 and 1884, the first two over attempts to introduce an 8 hour working day. In 1874 Talargoch had a total of the following steam engines in operation: One x 100” (at Clive Shaft), one x 80”, one 36”, two x 24”, two x 18” and two x 12” plus 15 donkey engines. They also had a 20 foot diameter waterwheel and another of 40 foot. Accurate temperature readings were taken at a depth of 630 feet in 1880. These showed an increase in temperature of 1 degree Farenheit for every 77 feet below the surface. The mine worked three principal veins of which the longest was nearly a mile in length. They are Pantons Vein, Talargoch Vein, and South Joint. Panton’s and Talargoch are separated by, and run parallel to, the Prestatyn to Meliden Road. These rich veins are terminated by the Prestatyn Fault before reaching Bishop’s Wood. The veins worked in Bishop’s Wood are minor, with limited mineralisation and are consequently not extensive. Two miners cottages (2 storey) remain behind the mine office (now a residence) as part of the 4 or 5 house terrace of Talargoch Cottages. On the wall of one of these is a plaque stating: “[Built] at the expense [of the] Talargoch Mine Co. MDCCLXXXV” In 1875 the mine was for sale as a going concern for an asking price of £50,000. There were no buyers until 1883 when it was sold for £4,600. The pumps were turned off when mining ceased in 1884. A few men were then employed until 1899 when the last six men finished work underground. Presumably these men were removing the last remaining equipment before the entire mine flooded.

The waste

tips were worked for a few years after closure which continued to produce

zinc ore up until 1905 when the final 29 surface workers were laid off.

There was an attempt in 1903 to seek funding for further mining at

Talargoch by Captain Matthew Francis but nothing came of it. A letter from Talargoch lead miners dated 1850 was sent during the strike seeking support (Courtesy of Flintshire Record Office)..................... Talargoch Mines 4th August 1850 Mr Jones, Dear friend, we, the Talargoch miners do stand out against oppression and tyranny and our masters put on us as miners. We stand out manly like one man since last Saturday month. God knows what is the purpose of this, we have given every fair proposal to the masters but all in vain hitherto. They also refuse every offer coming from the miners hands. Now what are we to do in this case - we have lost the poor miners Fund in order to aid the weak amongst us. The gentry and clergymen give liberally towards it i.e. the Fund. And so this time we come upon your asking as miners and masters. If you are men that will sympathise towards your fellow creatures, helping will exhibit your liberality towards men who have been suffering for want of food, together with our little children, these last 4 months have been venturing without any prospect of half a penny to support our human nature and relieve our misery. We should feel ourselves much obliged to you for the smallest boon. Please to send with the post your opinion upon this subject to us.

For the

miners: William Michel, Thomas Morris, George Harrison

(Note: ‘Venturing’ in this context describes mining on their own accord, as distinct from working for the company. Although this word is used in the letter, most secondary sources appear to omit it entirely).

Cris Ebbs

Main sources: Thornburn, J.R. (1986) Talargoch Mine. British Mining No 31. Monograph of the Northern Mine Research Society. Morris, Kathleen Lloyd (1990) Talargoch Lead Mine The Mines of Flintshire & Denbighshire (Mineral statistics 1845-1913) 1992 The Geology of the Coasts Adjoining Rhyl, Abergele & Colwyn. Strahan 1885 The London Lead Company in Wales. J.N.Rhodes Special Report. Bernard Smith 1921

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|