Navigation......................................

01.

Home

02.

General Lead Mining History

03a. Halkyn Mines: History

03b. Halkyn Mines: A few artefact photos

03c.

Halkyn Mines: info downloads

03d.

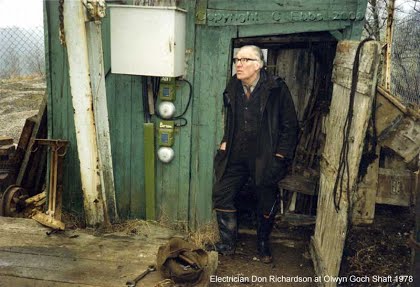

Halkyn Mines: Don Richardson - electrician

03e. Milwr Tunnel: Recent work

04.

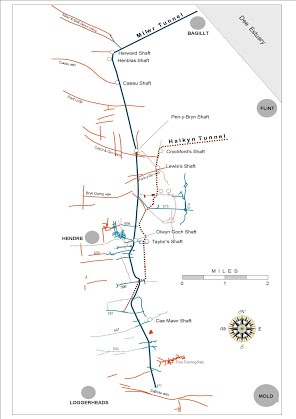

MAP: Veins of Halkyn Mountain

05. Blaen-y-nant vein, Eryrys

06. Westminster vein, Eryrys

07. Fron Fownog Flats, Gwernaffield

08.

Pilkington's vein, Loggerheads

09.

North Henblas Mine, Milwr

10.

Deterioration of the mining record

11. Talargoch Mine

A.

Mines lighting old & new

B. Links

C. Further reading

D. Cris's Shop Window

03a. Halkyn Mines: History

The most extensive mine complex in Flintshire & Denbighshire was that created by Halkyn District United Mines, a company first formed in 1928 by amalgamating several existing mining companies. The company was created to continue the driving of the areas deepest drainage adit known as the Milwr or Sea-level Tunnel, which was commenced in 1897, but stopped where it had reached the limits of its mineral boundary under the hamlet of Windmill near Halkyn. This tunnel today runs from Bagillt near Fflint on the Dee Estuary for 10 miles to the hamlet of Cadole some two miles to the west of Mold. It successfully drained over 50 veins and created a labyrinth of over 60 miles of interconnected passageways. At a time when low ore prices were crippling the industry nationally, the working of new and existing ore deposits during the 1930's ensured that up to 650 men were employed by the mine and tunnelling records were being broken.

Initially the company set up a large mill at Pen-y-Bryn Shaft near Halkyn,

but as the Milwr Tunnel continued southwards, it became necessary to move

the mill to Olwyn Goch Shaft at Hendre. A further move was planned to Cae

Mawr Shaft near Pantymwyn. Although this shaft was enlarged in

preparation, the mill remained at Hendre until closure.

"To this day, the Milwr Tunnel sustains an average flow of some 1.2 cubic metres a second (with peak flows up to 4.4 cu.m.s), making it the most prolifically yielding mine drainage adit in Britain (and one of the most prolific in the world)”. Source: Mather, J.D. (2004) “200 Years of British Hydrogeology” Published by the Geological Society, London ISBN 1-86239-155-6

Click to enlarge

Map showing the area mined by Halkyn District United

Mines and the veins worked.

Three figure numbers represent lode numbers.

Part of an explosives box found in 2018 in Lode 702

Photo: George Harvey

The following are just a few chapters from the book: 'The Milwr Tunnel - Second Edition' (see "Cris's Shop Window" on left for details), with one or two small additions.......

Tunnel Progress before the formation of HDUM

The Milwr Tunnel was begun in July 1897 from a point 9 feet below high water mark at Boot End near Bagillt (SJ 213760) by the Holywell-Halkyn Mining and Tunnel Company. A self-acting flood door was installed to prevent inundation by the sea at high tide: A high tide pushed the door closed causing tunnel water to be diverted into channels and lagoons along the salt marsh. Mining of the tunnel began south-westwards towards Herward Shaft (SJ 196740). At the same time an intermediate shaft was sunk (SJ 204749) from where two headings were driven, one towards Herward Shaft and the other to meet the crew driving from the portal. Thus the tunnel was being driven from three different points simultaneously. When both drivings met, the centres of each were only one inch out of true, a tribute to Mr N.R. Griffith of Wrexham, the Engineer.

The tunnel gradient is 1:1000 throughout. It is initially circular in section, 8 feet in diameter with a channel for water in the floor 1 foot 6 inches deep by 6 feet wide. Rails were laid on timbers above the water channel. The tunnel walls are brick lined for 1.5 miles where the tunnel passes through shale and coal measures, but thereafter is in chert or limestone and is generally self-supporting. 307 yards north-east of Herward Shaft, a branch tunnel known as the North Cross was driven north-west to intersect the Beili Gwyn and Old Milwr Veins. The tunnel south from this area changes to a square section of 8 feet x 8 feet. From Herward Shaft the tunnel passes through Milwr Mine for a short distance to Caeau Shaft on Caeau Mine (SJ 195729) where driving stopped 2 miles from the portal in 1908 at the limit of the company’s mineral boundary. The tunnel, at this time, drained an average of 1.7 million gallons per day (gpd) or 8,000 tonnes. The fastest rate of tunnelling was 54 feet a week. The veins cut by this section of tunnel are, from north to south Pen-yr-Hwylfa, Dolphin, Drill, Coronation and Pant-y-Pydew or Caeau Vein. The Old Hwylfa Vein was drained by a higher level cross-cut driven from Milwr Mine as this lode could not be traced at tunnel level.

NB The text

on the photo is incorrect: The view is actually looking east along the Pantymwyn Vein (Lode 547) midway between the Milwr Tunnel and Cae Mawr Shaft.

With thanks to Nick Carter for the information

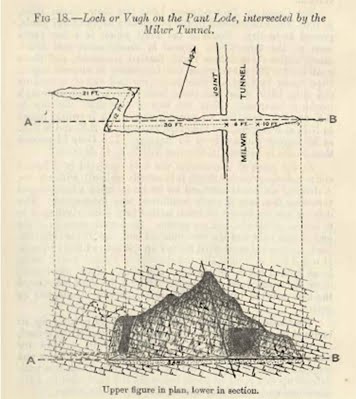

In 1913 an Act of Parliament allowed the company to continue driving the tunnel which reached this extended mineral boundary in 1919 at the hamlet of Windmill on Halkyn Mountain. The Act enabled the company to mine without legal challenges from land or mineral owners, whose property the tunnel passed through. Rates of advance of 40 to 45 feet a week were achieved during the early years of the First World War. A two shift system was operated; one drilling, the other for shooting (blasting) and ‘mucking out’: The drilling team consisted of three drillers and one ‘spanner-man' working on the face together. Each charge or blast gained an advance of 4 feet. The average cost per foot was £2-6-8d compared with £4-2-6d a foot spent driving the northern brick lined section. During this southerly advance, the Erw Vein was cut where water of about 1,400 gpm entered from natural fissures. Grainger's Vein, the Pant Lode and what may have been the Old Chwarel Las Vein were also intersected. Upon reaching the company’s boundary in 1919 Caeau Shaft was sealed off and all work on the tunnel was again halted. At the intersection of the Pant Lode, a flooded cavern, known locally as a loch or vugh, was cut at 6am on 5th January 1917. This caused St Winefride’s Well at Holywell, 2.5 miles to the north, to run dry 11 hours later. The burst of water swept loaded trucks along the tunnel until they jammed and sand blocked the tunnel, being 2 feet deep at the entrance, seriously hampering progress for many weeks. Water levels in a number of neighbouring mines were also affected.

The water issuing from this vugh eventually decreased from 10,000 gpm to a steady flow of 4,000 gpm from feeders on the east and west of the tunnel. Interestingly, the water temperature of the east feeder was about 49 °F, whilst that from the west was 56 °F, suggesting the warmer feeder passes through a deep-seated aquifer. As the water at St. Winefride’s Well was an important source for local industry at the time, pumps were installed at depth in Roskell's Shaft at Holywell (SJ 180765) as an alternative supply. Roskell’s Shaft adjoins the Holywell Boat Level whose portal (SJ 184764) lies near St. Winefride’s Well. Halkyn District United Mines

Following a takeover in 1928 by the Halkyn District United Mines Ltd (HDUM), Caeau Shaft was re-opened and the 5,000 feet to the tunnel face at Windmill was reconditioned to cope with the large volume of water now flooding the rails. The tunnel floor was sectioned off and one side filled with debris from the face upon which the rails were laid 3 feet above the original floor. As this reduced the walking height of the tunnel, ten pit ponies of not more than 12 hands were purchased, three to work each shift of eight hours with one in reserve. A pony hauled 3 or 4 trains each shift of 5 wagons weighing 5.75 tons per train, the slight gradient making the task less onerous.

The tunnel now rapidly pushed south beneath the hamlet of Catch reaching Pen-y-Bryn Shaft (SJ 202707) in July 1929. Surface operations were transferred to Pen-y-Bryn the following month. This shaft measured 9 feet by 7 feet by 800 feet deep. It was fitted with two cages in balance each holding 8 men or one loaded mine wagon or tub. The cages were hoisted by an 80 horse power electric motor through double gearings onto double cable drums 5 feet in diameter. Shaft signalling was controlled by two men: the banksman on the surface and the onsetter at shaft bottom.

Driving south from Pen-y-Bryn Shaft the tunnel was then driven larger in section being 10 feet wide and 8 feet high. A water channel, known by an American mining term as “the grip”, was cut to one side of the tunnel 4 feet wide and 2 feet deep. A major branch tunnel was driven east from a point three quarters of a mile south of Pen-y-Bryn. This was driven for one mile to Rhosesmor where lodes 674 (Barclay’s) and 675 (Powell’s) yielded major deposits and were worked successfully for many years. Three quarters of a mile south of this branch tunnel, the main tunnel intersected lode 656. This previously unknown vein was the first to provide healthy profits for the faithful shareholders of Halkyn District United Mines. As the tunnel progressed southwards towards Hendre, an old shaft now known as Olwyn Goch (SJ 201677) was enlarged to 12 feet by 12 feet 6 inches and deepened to 470 feet. During this work it was found that the original shaft was not vertical and was 8 feet out of true at its bottom. The tunnel reached Olwyn Goch in 1931 and in 1934 surface operations were transferred from Pen-y-Bryn to Hendre.

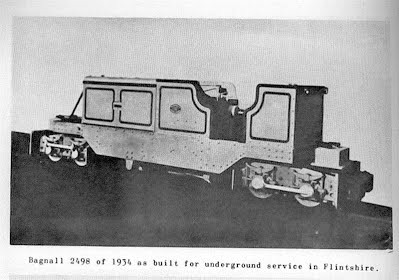

Rare photo showing the original livery of loco 2498

Taken from Bagnall's catalogue and kindly supplied by

narrow gauge historian Vic Bradley

Ruston Hornsby loco RH 183727, photographed by P.

Hindley in 1967. Kindly supplied by Vic Bradley

Olwyn Goch Shaft had a similar hoist to that of Pen-y-Bryn but had larger cages, each carrying 16 men or 2 mine wagons. At this time Olwyn Goch was chiefly used for raising men and materials, until the 1940s when limestone quarried underground was raised here. At the same time Pen-y-Bryn Shaft was being used for winding ore and materials. The speed of winding at both shafts was 710 feet per minute or 8 miles an hour. At the surface close to Olwyn Goch Shaft were the offices, changing rooms, bath houses and lamp rooms sufficient for 500 men. The shaft top was situated on the hillside above the buildings, therefore a passage was driven into the shaft from a point immediately behind these buildings for easier access. Fixed ladders, supported by platforms in the side of the shaft, also provided an alternative route to surface for the men in an emergency. By 1938 the tunnel had reached lode 547 (Pant-y-Mwyn vein) when low ore prices once again halted progress. All but 40 of the 650 men were made redundant and an era of great productivity drew to a close. With work on the tunnel at a standstill, a little prospecting was being done during 1938. The continuation of lode 630 was sought beyond a cross-course (fault) and found by a team led by the new foreman, John Bellis. In 1939, Pilkington’s of St. Helens became interested in the high grade limestone of the mine for glass making and work began excavating large quantities of the stone, chiefly from the area to the west of Olwyn Goch Shaft, near the hamlet of Hendre. This limestone was also used for agriculture and as an ingredient in toothpaste. Ore was shipped away for smelting as all the local coastal smelters had closed before the 1930s. Ore was shipped to Avonmouth or Chester. The Chester smelters 'Associated Lead Manufacturers Ltd' handled Halkyn's ore in the later period.

Small enamel sign

Excepting during the war years, when lead mining would have taken

priority over limestone, this underground quarrying continued until

1969 and resulted in a series of impressive chambers, some up to 80

feet high which, if joined end to end, would extend for 2 miles.

Limestone output was 70,000 to 80,000 tons per annum. A jump in ore

prices in 1948 prompted renewed activity at the main tunnel face and

after a 10 year stoppage, it advanced south beneath the Hand Inn at

Gwernaffield. A new lode, 538, was cut here, but contained very little

ore. Further south however, lode 530 was discovered, which was rich in

ore and provided work for 10 more years. Mid-way between Gwernaffield

and Cadole during the 1950s, the tunnel struck lode 524 (Pant-y-Buarth

Vein), followed by lode 501, both rich veins which were worked until

the tunnel reached its present end in 1957 at lode 477 (Cathole Vein)

just yards before the Mold-Ruthin road. Lode 477 was unproductive at

this point but a feeder brought in large volumes of sand and clay with

water from natural cavities above. Miner Walter Block of Mold stated

that “enormous quantities of sand were washed down the tunnel

amounting to thousands of tons and tubes of clay were being forced

under great pressure into the tunnel”. No lead was mined from 1958 to

1964 when work centred on the limestone mining at Hendre. A final jump

in ore prices in 1964 kept the few men busy until 1977 removing ore

from the existing lodes when the workforce never exceeded 40.

Thereafter work revolved around maintenance and tunnel repairs until

final closure in 1987. The

lead mines of Flintshire, since records were first kept in 1845 up to

the first world war, produced a total of 400,000 tons of lead ore and

over 100,000 tons of zinc ore. Since then, the Milwr Tunnel and

associated lodes have produced a further 200,000 tons of lead ore and

around 80,000 tons of zinc ore, the majority of this being extracted

prior to 1957.

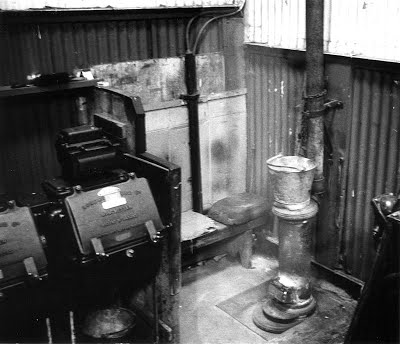

Empty waggons at Olwyn Goch Shaft 1976 Simple seating and stove in a corner of Olwyn Goch winding house in 1978

Men ready to descend Olwyn Goch Shaft 1976 Olwyn Goch shaft bottom in 1978, shortly after the shaft signalling system had been modernised

Miners beside an Eimco digger in the drift off the Milwr Tunnel leading

to Cae Mawr Shaft (at Gwernaffield)

The last mining for galena, on Lode 524 (Pant-y-Buarth) in

1976 Photo: Chris Williams

The Mill at Olwyn Goch

By the mid-1930s Olwyn Goch had taken over from Pen-y-Bryn as the centre of operations. It was equipped with an elaborate milling complex to process raw material and all the necessary infrastructure to ensure maximum working efficiency. A First-aid room and First-aid lecture room were provided as well as separate heated changing rooms for management and miners. The Underground Manager was provided with his own office, bathroom and lavatory. Cycle and motor-cycle sheds were also provided.

The site had a canteen, workshop, carpenter’s shop, blacksmith’s shop, a mechanical department office, electrician’s shop, rip bit shop, stores and survey office. The survey and drawing office contained the company’s large collection of old mine plans. A fully equipped laboratory regularly sampled and monitored ore quality and geological specimens.

The site was linked to the Mold-Denbigh railway line by sidings and a weighbridge was built for road haulage. A man arriving for work would change, collect his charged lamp and place an individual numbered brass tally to indicate their presence underground. He would then walk along the short tunnel leading to Olwyn Goch shaft to be lowered by cage into the mine.

On very icy mornings at the main shaft, it was common practice to lower and raise the empty shaft cages several times to remove any dangerous icicles hanging in the shaft. Despite this precaution, the first men down had to endure “the disturbing sound of crunching and cracking” during the descent. In 1975, a major rock fall seriously damaged the ladderway in the shaft and most of the ladders and platforms were replaced with best quality timber. The oak ladders are in remarkably good condition today.

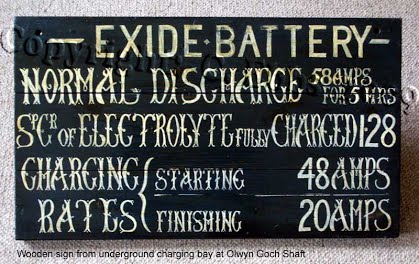

The sign above was found in a poor state and is shown in its restored condition

The Workforce

The great majority of the workforce were new to metal mining and had to be trained. A mine survey in 1934 showed that of 600 men, only 17 had previously worked in lead mines of the area and of these, only 12 were fit for underground work. The turnover of miners was quite high and during the late 1930s many of the workforce came from the slate quarries of Snowdonia such as Maenofferen, Penrhyn, Llanberis and Trecastell. Others came from local collieries at Bagillt, Buckley and Nerquis (Nercwys). Employment records show that many of these men were aged over 60, some of whom continued working underground to the age of 70.

Although some men were ex-colliers, conditions in the lead mining industry were so different that it was considered that "a coal miner in a metal mine was sometimes a menace". Training was therefore essential and continuous and meant that some working methods had to be simplified. In general one man learnt one job. Shift foremen were usually promoted from the ranks. Miners were issued with a small book of rules outlining rates of pay and requirements of the job. Attempts were made to employ graduate foremen but this was unsuccessful. Each group of lodes known as a ‘mine section’ had a Section Manager or Mine Captain who, in turn, was responsible to the Mine Manager.

A shift system was operated from midnight on Sunday to Saturday afternoon. This gave men the opportunity to work 17 shifts in three weeks. It also ensured that mining was continuous for 138 hours a week. The average wage in 1936 was £3-12-6d a week payable each alternate Friday. Should a safety man be unlucky enough to have an accident occur in his section, he would be deducted 2s-6d for each absence of three or more shifts. Surface mill workers at Pen-yBryn would average £2-12-0d a week which included an efficiency bonus. Wages accounted for two thirds of the company's total expenditure. Glynn Morris, photographer, once worked for HDUM. Responsible for drilling machines and drill bits, he was known as a ‘steel nipper’. Mr Morris described an incident when a miner alone in the Halkyn Lode suffered a lighting failure. “He was lost for three days”. Since that time company policy dictated that men should work in no less than pairs. Mr Morris also described the operation of raising loaded wagons at Pen-y-Bryn Shaft: “The underground passing place for locos was called ‘The Shunt’. The onsetter’s job (underground) was to push loaded wagons into the cage which would push out the empty tub on the opposite side. The banksman (surface) would push out the loaded wagon which ran down a slope to ‘The Creeper’. This was a chain hauling device which pulled the tubs up a slope to the tippler, where ore was tipped onto the jigs. When 40 or 50 empty wagons were ready (had been lowered underground), the loco took them away”.

The highly profitable Powell’s Lode was named after Captain Edward Powell, whose mining family had moved from Dylife in mid-Wales. The title ‘Captain’ was commonly applied to the respected post of mine manager. His gravestone can be seen today at Halkyn Church. Captain Powell’s son Joseph had a daughter who Glynn Morris married.

The men were generally well cared for but a strike in 1934 resulted from moving the centre of operations from Pen-y-Bryn shaft at Halkyn to Olwyn Goch shaft at Hendre, some two miles to the south. The Manager at the time, Mr J. B. Richardson told the men "You can stay out as long as you like, I have bread forever". When the men eventually returned to work, it was for one shilling a day less than before the strike. Despite this disagreement, the mine was regarded by the men as a happy place in which to work. Modern Exploration

After closure a water company acquired water extraction rights to the mine complex. This company now supplies industry on Deeside from the flow issuing at the portal in Bagillt. In 1995 mine enthusiasts from a local club negotiated an access agreement. They then began a programme of exploration which at the time of writing, has resulted in over 26 miles of workings being examined.

Initially, exploration centred upon the lodes at Milwr Tunnel level. These workings are distinctive in that all ore and accompanying minerals were entirely removed from the lodes for separation on the surface. This resulted in large open stopes, typically 2 or 3 metres wide and frequently over 65 metres in height, being perhaps half a mile in length. Lodes were extracted upwards in this manner until the ‘old man's’ workings were encountered above or until the ore pinched out. In the older workings, only ore and perhaps a minimal amount of waste rock was removed, resulting in smaller passages but more interesting workings. As a general rule, the higher the workings above Milwr Tunnel level, the older they are; workings closest to the surface possibly date back to Roman times.

It soon became obvious that 1930s rotting ladders could not be relied upon to reach the higher workings. A method was therefore evolved requiring a 5 metre aluminium ladder and a battery-powered drill. After climbing the ladder, a bolt with ladder-bracket could be fixed to the stope wall. Suspended in his sit harness at the top of the ladder, the operator could then raise the ladder and clamp it onto the bracket in order to gain another 5 metres and so on. Having reached old workings above, permanent rigging would then be installed for future trips. Due to the length of exploration trips being carried out, alternative entrance points became necessary. Permission was sought and two old shafts were re-opened to act as emergency exits. These shafts also provided sporting through-trips; one being a 500ft deep shaft at Pantymwyn, the other a 650ft deep shaft at Halkyn. Both shafts were rigged for rope descents and ascents.

A new telephone line was laid the two miles from Olwyn Goch Shaft to Powell’s Lode Cavern and the club installed several underground emergency stores with ration packs and first aid equipment.

After more than twelve years work in the complex, several areas of higher workings have been made accessible and numerous round-trips can now be undertaken. Grosvenor Caving Club consequently arrange regular trips for visiting clubs from throughout the UK, in which over a hundred suitably experienced groups have so far taken part.

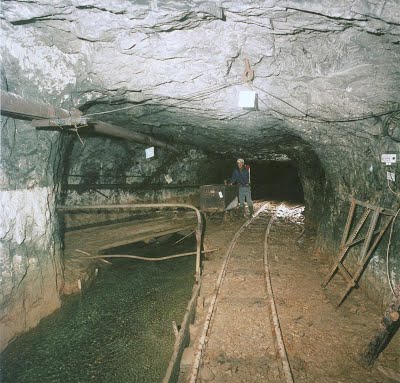

Further work has been carried out to repair nearly three miles of rail

track. The original locos were in a poor condition, therefore a new

diesel loco in kit form was built by club members and lowered down the

entrance shaft. It was assembled below ground and now carries visitors

to the cavernous limestone workings below Hendre or to Powell’s Lode

Cavern beneath Rhosesmor.

View across the 'bottomless' lake in Powell's Lode Cavern Photo by Paul Deakin

Powell's Lode

Cavern beneath Rhosesmor

Photo by Paul Deakin

Access along the main tunnel can be ‘dry walking’ during the summer

months, but in wetter weather the grip overflows covering the rails

and making walking almost impossible over long distances. In contrast

however, most of the lodes are dry and dusty places, involving no more

than ambling along roomy open stopes, or perhaps stepping over piles

of dry rotting timbers which have fallen from high overhead. Most of

these lodes still exhibit timber ladder-ways and ore chutes together

with the occasional abandoned mine wagon. The older workings above

contain artefacts such as hand winches, bell-signalling devices, a

wooden candle box, a compressed air winch, a wall-mounted carbide

lamp, etc.

One of the more interesting areas is accessed from a point half way down Olwyn Goch Shaft: Stepping out of the shaft into old workings, a branch of the nearby Halkyn Tunnel is entered. This was driven specifically to drain the old pre-1880s workings just north of the hamlet of Hendre. These workings, due both to their age and the fact that they are ‘flat’ (near horizontal) workings and not vertical veins, are entirely different in character to those already mentioned. Most of this area can be seen on a four hour round-trip passing two interesting old drum winches, one of which was operated by compressed air. Underground stables once existed nearby, but these have now been lost due to surface quarrying.

Much of the five mile long Halkyn Tunnel can be visited, but this involves longer trips typically taking 10 hours or so. The route from Olwyn Goch at Hendre involves walking north (if the train has departed) for a mile along the main tunnel, then following a branch tunnel east for another mile. Prussiking is then required to ascend 55m through old workings above Powell's Lode, from where a further four mile round-trip begins and ends. The journey passes through Rhosesmor Mine, the Halkyn Tunnel and East Halkyn Mine. Items to note en-route include a passage wall where old miners signed their names, two sets of electric pumps installed in 1907 and 1908 (used to drain the mine in the days before the Milwr Tunnel had reached this area), old timber wagons abandoned a century earlier and a wooden peg counting board for recording up to one hundred loads, situated at the top of a steep incline. Here an operator once spent his shifts lowering wagons loaded with ore down to the Halkyn Tunnel below. The drill carriage above was originally fitted with four flanged wheels to enable it to be moved on rails. Once in place, the wheels would be removed and the main threaded shaft would be tightened between floor and ceiling to fix the device firmly in place. Drilling machines were then attached to the mountings shown. The drilling rigs of the 1930s were far lighter and easier to move.

Artefacts & Papers

Although it was general policy to remove equipment from exhausted lodes, a surprising amount still remains scattered throughout the workings today. The loco track from Pen y Bryn to within half a mile of Cathole Lode and along the Rhosesmor Branch is completely intact totalling over 6 miles. At Olwyn Goch Shaft in the main tunnel lie two diesel locos, a loaded train of about a dozen wagons, a double bogey rail transporter and a diesel truck for fuelling the locos. The compressor chamber in this area was turned into a workshop in later years and although most equipment was removed, much in the way of spanners, jack-hammers, work-benches and fittings still remain, although dry-rot has now destroyed most of the timber benches. The charging bay beside the workshop is almost complete and exhibits batteries connected ready for charging.

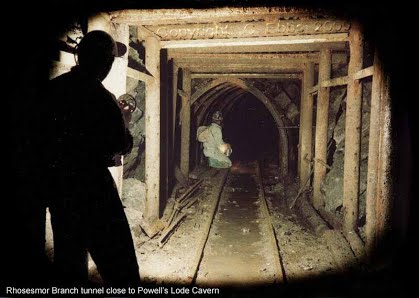

Junction of the Rhosesmor Branch Tunnel with the main

Milwr Tunnel

The water channel takes water from a natural cave

system that supplies the lake in Powell's Lode

Photo by Paul Deakin

At Pen-y-Bryn Shaft lie two man-riders and a covered truck used for

the conveyance of the mine manager specially built for the purpose.

The limestone workings west of Olwyn Goch also contain up to 40 mine

wagons together with several Eimco rocker shovels. Not to be

overlooked are the areas used by miners for discarding rubbish. At

such places can be found old boots, cigarette packs, old tins and

newspapers dating back to the 1930's. The onsetters cabin at Olwyn

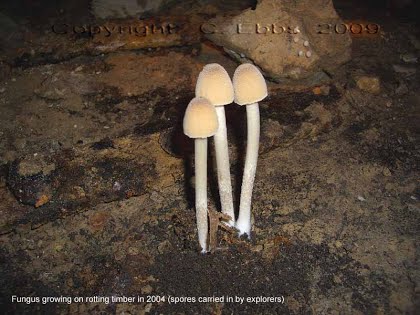

Goch Shaft has oilskins hanging on a hook on the wall, but the table

was consumed by fungal growth within a few years of the mines closure

in 1987.

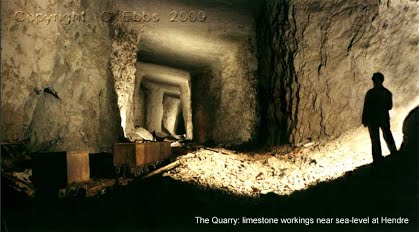

"The Quarry", an area covering several acres of such chambers mined

for high quality limestone.

Photo by Paul Deakin

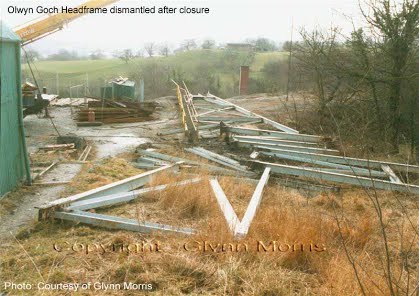

Little remains on the surface as all headframes have now gone and all

shafts connecting with the tunnel have been sealed off. At Olwyn Goch

Shaft a few office buildings and a milling shed remain, but their

contents were removed prior to closure. The winding shed at Cae Mawr

Shaft near Gwernaffield still exists. This housed two winding drums

with cables, but they were dismantled for scrap early in 1993.

Mining enthusiasts hoped prior to closure, that a show-mine could have been developed at Olwyn Goch Shaft utilising the original 1930's equipment, but apparently none of the bodies consulted could be persuaded to act. Club members have saved or restored numerous threatened artefacts. These remain in private hands awaiting the creation of an appropriate local museum.

Before closure Halkyn District United Mines Ltd deposited their collection of mine plans with the Mines Records Office. These are now available for public viewing at the County Record Office, Hawarden (Ref: D/HM). A Record Office catalogue entitled ‘Holywell-Halkyn Mining & Tunnel Co Plans’ lists the 354 mine plans and maps available. These not only cover Flintshire mines, but also some in Denbighshire and a few in Cardiganshire, Caernarfonshire and Shropshire.

Club members have also managed to obtain a considerable number of documents relating to Halkyn Mines. These include blueprints and drawings of many items of equipment together with 1930s and 1940s manufacturers’ equipment catalogues, employment records and many ‘Standard Drawings’. Further documents include company inventories for 1936, 1938 and 1941. These describe every single item owned by the company from derelict engine houses to tea-cloths. They provide a detailed insight into day-to-day workings of the mine. A database of the saved documents and of (some of) the artefacts found in the workings is held by the club (and can be downloaded from this site at the "Assorted Information" page). The 1941 inventory is currently on loan to Flintshire Record Office, Hawarden.

Artifacts continue to be re-discovered: In December 2007 Grosvenor Caving Club entered a remote area some 40 metres above the level of the Halkyn Tunnel in the eastern end of Great Halkyn Lode (East Halkyn Mine). Here miners had abandoned all their equipment. Amongst the items found were various drilling machines, drill steels, glass bottle, clay tobacco pipe, various tools, rails and wagon, safety fuse with crimping pliers, shovel, tin box, metal water bottle, compressed-air windlass and an air pressure gauge. A date of 1898 was found on a passage wall nearby with the name of miner 'B. Hough'.

Where did the headframe go?

The headframe from Olwyn Goch shaft, together with the winch, winding

shed, and other equipment were dismantled soon after closure. They can

now be seen in their glory at Dolaucothi Gold Mine in mid-Wales. Some

excellent photographs can be seen here: http://www.ukurbex.com/index.php?/topic/116-dolaucothi-gold-mine-west-wales-10/

Explorer Access

When the mine was still operating in the 1980s, a few explorers began

to examine the mine from Hendre Quarry, which had cut into the old

workings of North Hendre Mine, but this old entrance has now been

quarried away. The entrance led downwards and eastwards to a long

cross-cut which, in turn, led to Olwyn Goch Shaft at a point about 200

feet below the surface. After the mine closed in 1987, explorers,

faced with the prospect of no access whatsoever, began talks with the

owners and an agreement was eventually signed. This was subject to

several of the owners conditions including the setting up of a leader

system and of course, public liability cover for all visitors. This

system has operated well on this basis since 1995 as a result of the

efforts of Grosvenor Caving Club.

NB

For current access information, please contact Grosvenor Caving Club. Contact details can be found by scrolling down this page: https://sites.google.com/site/cavesofnortheastwales/

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust describe the mine thus:

Halkyn District United CPAT Historic Environment Record number 18015, grid reference SJ20307070.

Workings In 1928, the Halkyn District United Mines Ltd began to extend the sea-level tunnel. The Company was the amalgamation of nine old mining companies and two drainage companies. The sett worked eight main veins off the sea-level tunnel and covered an area of 25sq miles, from Windmill to the south of Eryrys. The main shaft and mine area remains in the Wimpey Asphalt Pant Quarry. Referred to as the New North Halkyn Mine and the Pen-y-bryn Shaft, it was sunk to 800ft to raise ore and acted as the main shaft on the Holywell-Halkyn Drainage Tunnel (previously known as the Deep Level Tunnel). The Pen-y-bryn Shaft was an upcast shaft for the ventilation system. A shaft to the south of the main shaft was located at SJ20257055. To the north-east of the main shaft, a shaft was located at SJ20367083.

NB The misleading description above seems somewhat at odds with what is known of this major mine company. Furthermore, the main shaft on the Deep Level (or Halkyn) Tunnel was Lewis's Shaft at Halkyn and not Pen-y-bryn as stated. A large milling complex existed at Lewis's Shaft prior to the driving of the Milwr tunnel through the area and a passage was driven north-west in search of ore from Lewis's to Pen-y-Bryn in 1905-6 (at a depth in Pen-y-bryn of 609 feet), but little ore was found. The Holywell-Halkyn Drainage Tunnel was also known as the Milwr Tunnel or the Sea-Level Tunnel. It was driven from sea-level at Bagillt for 10 miles to Cadole. The Deep Level Tunnel (named after the Deep level Lode at Halkyn) was also known as the Halkyn Tunnel, the Old Drainage Tunnel or the 1875 Tunnel. It was driven from 180 feet above sea level from near the town of Fflint for 5 miles to Pantymwyn.

Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust carried out a 'Clwyd Metal Mines Survey' and have an index of mines on-line at: http://www.cpat.org.uk/projects/longer/mines/mines.htm Some entries such as that above contain significant factual errors and show a limited understanding of the underground workings and arrangement of veins. Researchers should therefore treat entries with a degree of caution.

|